Flat Panel Cabinet Doors

Using solid wood or veneered MDF for panels. April 18, 2004

Question

All of the cabinets I've made have had raised panel doors. I'm about to make some cabinets with Mission style, flat panel doors. What is the best way to make the flat panels? Is re-sawing solid wood down to get 1/4" thick panels the best way to go, or should I go with 1/4" veneered MDF?

Forum Responses

(Cabinetmaking Forum)

From contributor D:

For whatever you do, don't try to plane solid wood down to 1/4". That does not work. You can use 1/4" plywood, however, plywood never seems to stain very well. We plane our panels down to 1/2", put a raised panel edge on just like a regular door panel, but turn the raised side back and the flat side to the front. This will stain a lot better.

From contributor B:

The 1/4" solid wood panel is not the best way to go. You could veneer the MDF as you have suggested, or even find a 1/4" plywood in the species of your choice. The thin veneer on plywood needs some attention in regard to applying stain, as the veneer often seems to stain much darker than the rails and styles.

From contributor T:

I shopped out most of my doors. Not the best idea, but I did it. Some door manufacturers offer a 3/8" solid flat panel, which is very acceptable. I have had serious problems taking a traditional raised panel door and turning it around for the flat side out. The customers do not like this. They open the door and see that raised panel on the inside and they go crazy. Two wound up in court over this issue. Very bad. Needless to say, those jobs were big losers.

From contributor M:

I like to use a 1/2 inch solid panel and just rabbet a 1/4 x depth of the slot in the door rail on the back side. Same effect as a backwards raised panel, but I think it looks much better. The face of the panel ends up basically flush with the back of the door. If you use space balls to hold the panel centered, you'll get a nice even reveal between the door frame and the step on the back panel.

Contributor T, I'm curious about your comment that outsourcing doors wasn't such a good idea - why not?

From contributor N:

The only wood I was able to get down to 1/4" with success was maple. Oak, birch, cherry, and rosewood were a very expensive disaster. Veneer on MDF worked well but not on 1/4". I used 3/8" but had to veneer and finish both sides to prevent warpage on painted doors and I had problems with under-sink doors because of moisture.

After wasting countless hours and a fortune experimenting, I now outsource my doors to a well-equipped door shop with a good reputation. They back their product and frankly, I don't care what material they use, as long as I get the result I'm looking for. The owner of the shop I deal with told me the secret was in the sanding, that they use different grits of sandpaper and the veneer surface for stain to match solid wood. He told me it took him 12 years to get the proper combination. I guess I'll have to take him out and get him drunk to hear his secret!

From contributor T:

Contributor M, I'm more inclined to build the doors and drawers myself. This way I have control over the grain matching and just the idea of using what would normally be waste seems to me to be much more efficient than giving my hard-earned money to keep another business going that doesn't care whether the grain pattern on my doors match or not and when there is a call for service, it is always a matter of I didn't do something right because the door supplier is perfect so it must be me. I would get an obvious bad stain job and when I asked why it was taking so long to satisfy my order, I got the answer "You are not our biggest client." This drove me over the edge. But I was doing what I was told to do. I personally would not do it this way. I still believe that if you want it done right, you have to do it yourself. I've heard all the explanations of how the outsource guys deal in volume and can build the doors and drawers cheaper than I can and this is just before they send you a notice for a price increase. I know that nothing is perfect, but when I do it myself, I feel I can get it a lot closer than someone who really could care less about my clients or my reputation.

From contributor T:

I think a lot of my problem was that I couldn't find suppliers that were local. A few years ago I had a guy who made all my custom doors local and I could personally supervise my orders and I was very happy with the quality of his work and how fast they were. He played a game with the IRS and lost and ever since, I have had a tough time outsourcing out of state.

From contributor R:

I'm just finishing up a kitchen with 62 flat panels that were re-sawed, planed/sanded to 1/4 inch. Some of you strongly disapprove of this approach. Why is planing solid material down to 1/4'' for flat panels not a good idea? Have I left myself open for headaches down the road?

From contributor B:

My experience with solid panels that thin is that they have a tendency to crack. If the panels are fairly narrow, you may be fine.

Another debate with using solid wood panels is whether or not the 1/2" tongue/mortise that most router bits support provides enough gluing surface to hold up for the long haul. Of course, this would be true of any solid panel.

The seasonal expansion and contraction of the solid wood panel must also be of concern, for if any glue runout from gluing together the rails and styles would bond the pane, then they will surely crack.

I don't strongly disapprove of the 1/4" solid wood panel - I just think that one runs the risk of a higher volume of door/panel failure.

From contributor T:

We also would not use 1/4" solid due to its rigidity and there are finish problems with consistency of stain color, and the center panel was just too thin and cheap for high-end work.

From contributor R:

Contributor B, your comments about the 1/2 deep mortise/tenon... That is the depth I made them. Had I known better, I could have easily made them deeper. I cut the grooves and tenons on my Felder saw/shaper using an adjustable grooving cutter from Felder. I could have gone way deeper. I also have a slot mortise and maybe I should have made full M/T joints on the frames and 1/2 inch deep slots for the panel. I have to admit I thought with the lightness of the 1/4 panels that the 1/2 deep would be enough.

Contributor T, when you say rigidity, I assume you mean "lack of."

These cabinet were not stained with a clear finish. I thought the color of the panels, style sand rails was pretty good. I would have thought a door panel made from the same stock as the styles and rails would match as well as anything. I made flat panel doors using plywood and ran into color problems, and that's one reason I tried the solid panel this time.

By the way, this kitchen was never meant to be high-end. I built these for free for a long time friend who at the age of 64 is finally building his first home and is on a tight budget.

From contributor B:

I suggest that the thin solid wood panels would pose no issues with finishing. They should stain up just like the rails and styles. The greatest concern would be the splitting, at least for me.

In regard to the depth, I have some sources that state that a 1/2" mortise does not provide a sufficient enough glue area to accommodate a door with a solid wood panel. A lot of doors, even with the raised panel, boast nothing more, such as with the cope and stick joint, that essentially have no more than a 1/2" tenon.

I have not yet determined what route to choose for myself. I have tried both methods thus far and have yet to have any door problems.

The plywood panel makes a strong door, as the panel can be glued into the frame as the wood movement in sheet goods is minimal.

From contributor P:

Even using a plywood panel, I still would not glue the panel in. The frame still will need to expand and contract, and the also the plywood will expand and contract (not as much as solid wood).

From contributor N:

I agree - panels, be they flat or raised, should not be glued. Some door manufacturers use a felt strip to keep the panel in place.

The comments below were added after this Forum discussion was archived as a Knowledge Base article (add your comment).

Comment from contributor A:

Antique flat panel cabinet doors often has raised panels on the inside to achieve the necessary thickness to help avoid splitting. My better cabinet folks still make them that way. They are never glued to the frame, but left free all around so they can "float". If plywood must be used, a product sold in any good paint store that seals both the frame and the plywood inset before staining helps equalize absorption and control the inevitable color variation.

Comment from contributor B:

We try to stay away from plywood for panels. We have made our flat panels out of 5/8 or 1/2 and simply used a small profile back cutter. We make cabinet doors for the trade and make sure that the customer knows what they are getting. We also prefer to use a 5/8 panel so we can run all of our panel stock with a tounge and groove to prevent cupping down the road.

Comment from contributor C:

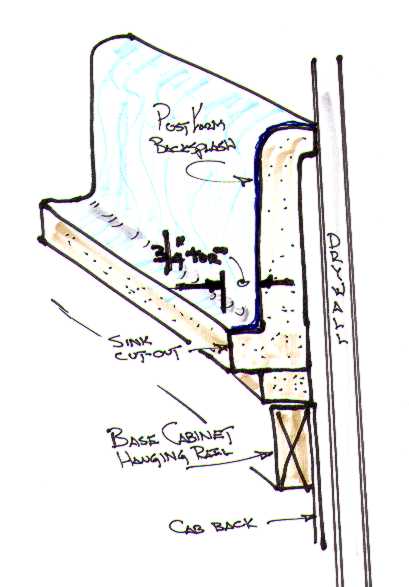

One way to make the door with wood instead of plywood is to plane the panel to 1/2" thick. Then rabbet the edge 1/4" thick by 1/2 inset into the panel edge. The rabbet is inserted into the frame so that the panel is inset 1/4" from the face of the door and sits flush with the back of the door frame.