Labor and Cost for a Complex Wood Window

The fine woodwork for a custom decorative window can be painstaking and slow. Here are some detailed thoughts on methods and the time involved (including an interesting description of doing the work with a CNC).June 12, 2013

Question

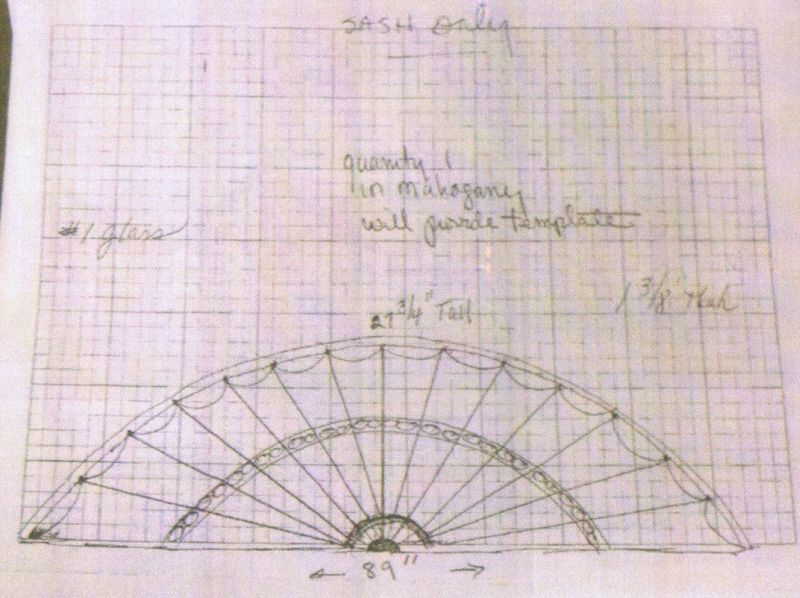

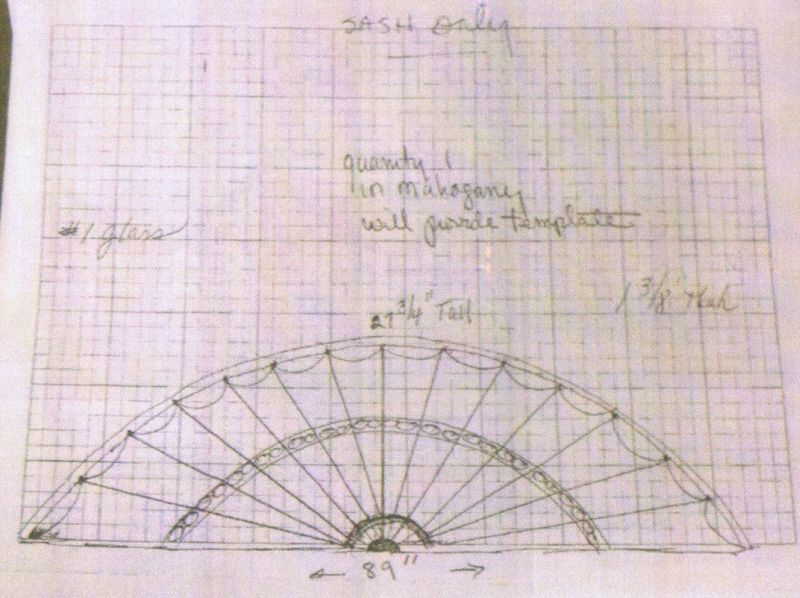

I am bidding on some window sashes and door slabs for a customer. The grids in the windows are a little more intricate then I normally do. I am looking for some ideas on how to price the job. These are hand drawings by the customer and are a little bit rough. All the lines in the window are wood mullions. We are basically a custom millwork shop - I am not set up to build windows production style. Window 1, I am thinking maybe 20 hours. Window 3, maybe 15. What do y'all think - am I way off here? Would you do an applied mullion or break the glass at each one?

Click here for higher quality, full size image

Click here for higher quality, full size imageForum Responses

(Architectural Woodworking Forum)

From contributor J:

Some of the factors influencing your time will be the rip or width of your mullion and the mullion's profile. Often, these Federal style sash mullions could get pretty thin. If you are pattern routing your mullions by hand this can get dicey real fast. The same goes for routing the mullion profiles. On the dormer sash, I would apply the beaded section and have the arches be actual mullions with glass breaks. Where the arches meet, they are usually mitered with a glue joint. Your main mullions can be stub tenoned or just coped and nailed. I have seen both versions on Federal windows and both can work. On the sidelights, I would consider laminating your mullion stock (in a brick fashion) to reduce your weak end grain on your circles.

All of this takes time, as does your full scale sketch on plywood to make your templates from. These will be beautiful sashes when you're done and are a testament to the skills of the sashmaker. I would allow more time and charge more money (especially if there is a profile on your mullions).

From the original questioner:

Thanks for your response. I don't know what the mullions will look like yet. I described to him what we usually do, but all that will have to be decided yet. I'm pretty sure there will be some kind of profile on them. I will be cutting them all out by hand on a shaper. I was figuring making a piece to hold the curved mullion on both sides to cut the end cope, but if I understand you correctly, you would just miter them into the stile?

From contributor L:

Window one I believe you are greatly underestimating your time factor. I made a window similar to this, but less webbing, and it took nearly 40 hours. All the cutting of the curves need to be precise and the copes at the end need to be exact and you will end up doing them again and again to tune them in. Window 2 is probably 2-3 days.

This is based on mostly normal equipment. When I was doing it I was using a MAKA mortiser, a Portrias single ended tenoner and 2 shapers for the stick and the cope. Lots of jigs to be made.

From contributor D:

I think 20 hours is more than optimistic - more like naive. More like 60 hours, with an experienced hand, with glass set (single glaze) and stops in place. The cope and stick for this must be very light, like 1/4" projection, or all those lines converge and muddy it up.

If there is to be insulated glass, you will have to have a minimum of 3/8" rabbet to hide glass spacers. 1/2 to 5/8" is more typical for IG units. 3/4" preferred for curved work. That makes your sticks net 1-3/4" wide. It will not look like he thinks it should.

I suggest you first explain to your customer that you will have to draw it full size, with all the sticking, and then show him how it looks. There is way too much going on.

From contributor B:

My initial reaction was that 20 hours for the first window was way too few. As the others, I think you are in for a minimum of 40 hours, thus requiring the pricing be based upon more like 50 to 60 hours.

From contributor M:

In regard to the mitered ends, I was referring specifically to the lacework arches along the top of the transom. They very well have a bit of a cope at the ends, but where they intersect with the next arch the mullion has a steep miter sawed into it. So the sequence would be to mill out the curved part, cut the angle of the intersection of the mullion to the rail, cope that cut, and then split the mullion where it intersects the adjacent mullion (what I have been referring to as a miter). This is all a heap of fun, but it does take a little time.

From contributor A:

I concur with the rest of the boys. I would go with 40 hours on #1 and 25 hours on #2. Did anybody else notice that #1 is 89" wide!

From contributor N:

Do you have a CNC? We used to do these by hand, but I found a better way. I plot this out on the screen, nest all the pieces on a couple of boards (utilizes the material way more efficiently), then plunge in, buzz out the shapes and profile them - all angles are precise and no hand fitting/messing around when assembling. Takes me maybe 15 minutes to write the program, another 15 to buzz it all out. My guys might take all day to assemble itů anymore and I get grumpy.

From the original questioner:

Well, I was a little naive in my hours there but my customer was too I guess. I figured 50 hours for window 1. There were actually about 15 windows on the whole job, all of them down the same line as those 2. Anyway, I called him with my quote and he says that is way over his budget. I'm not sure if he is just bluffing or serious but after all the help here, I don't think I am going down on the price. I really appreciate all the ideas you have given me.

We don't have a CNC. I used one about an hour away to do some work a little like this on some front doors (picture below). The problem with this guy is he mostly does cabinet parts and when it comes to this kind of detail, he doesn't do so good. I actually had to redo it all by hand with jig here. I guess we'll see what happens with the window job.

Click here for higher quality, full size image

From contributor D:

I'd like to hear more about how a CNC does those little curved parts in so little time. Curved blanks, profiled two edges, rabbeted two edges and coped ends, with double coped ends where the webs intersect the sash and radial muntins. And don't forget the glass stops. There are over 200 parts in the one sash.

The problem for shaper, overhead router or CNC is the same - some cuts are removing more than 25% of the total wood mass, both with and against the grain. Even if you can hold it, the parts tend to explode. Copes have to be done first, etc.

I have carried with me for years a small curved web part, with mitered coped ends, when I go to Atlanta or similar shows. I hand it to the eager salesperson, and then listen to him backpedal and eventually send me to another booth. I have yet to find anyone that can do those parts in one go. I agree that once the parts are made, assembly goes pretty quick with an experienced hand.

From contributor N:

My boss says I share too many trade secrets, but to make it less offensive - it took me several years to get that fast. Also I don't think he spec'd TDL, just a grid. I didn't learn this from a salesman at IWF, this is in house learned on the job. So, for grille bars 7/8" wide and 5/8" thick, your stock should be 7/8" thick. I have formula specs that will nest small arcs from 0 to 15 degrees from a line I draw. This line is from the two farthest points apart, so it gets nested as horizontally as possible, winding up with the least amount of end grain. The spacing from each other is automated so it also leaves enough room for router bits. Each tiny part has end work (copes) and profiling. The lines I color code so I can select them on the screen without actually clicking on each individual stupid line to apply a tool. I merely select a plunging cope tool, apply to all cope lines and hit okay, then the same for the profiles. I have different speed/feed lines for smaller arcs, taking a couple passes, the last one removing only 20 thousandths.

These are processes already programmed, ready to run, so I don't have to enter the numbers every time I program a sash. The maximum depth of plunge is 5/8", so it never goes all the way through the blank stock - no worrying about where to place pods, just throw it on there and run it. I remove the blanks after machining, flip them upside down at the widebelt with a 60 grit belt, run several passes through until I get to 5/8", at which point all the little pieces fall into a tray waiting on the outfeed. The guys don't even have a layout drawing - they just lay the pieces down like a puzzle. They are so accurate that no templates are needed. Notice I'm not making the perimeter sash here - someone else is bandsawing blanks and machining those manually while I'm on the CNC. I think two grids on that first sash would have in it maybe 10 man hours. We do sashes like this every day. TDL is way longer, maybe 20-25 hours for us.

From contributor L:

If you are doing a lot of the same size windows then you are only making your jigs once, and that part does take up a lot of time (jig making). And after you get the sequence down you could probably get the windows done pretty quick. It's just when you are making one or two of something that the jig to project time is bad.

If you have a guy that makes all the webbing in one or two days because they are all the same, then it might be a totally different pricing structure because at that point it does become production.

But you shouldn't reduce the value of your time all that much because you are making a bunch of them. You still have to develop the original prototype and they are usually 6-8 times the price of the production piece.

From contributor D:

Thanks for the explanation. Of course, a grid is a whole different animal. We don't do grids, all divided light (no "true" about it), so I tend to think only in divided sash work. Tell your boss you are okay and you deserve a raise. No trade secrets lost here. The AWI salesmen always thought I should quit divided sash and go with grids - so I could make real money. I learned early on to ask if they knew of any customers doing the work like in my hand. They said no one did that kind of work.

If there were 20 of these #1 windows, the numbers per each would go way down, as mentioned. I discount for multiples, but make sure it is reflected in my pricing. I can't do one for 1/10 of the price of ten. As mentioned earlier, these can't really be built as drawn, but it is a fun academic discussion.

From contributor N:

I think people can still benefit from using a CNC if their mind is open to it. For example making jigs - no more of that. The jig is the program. Its repeatability is nearly perfect and much quicker than by hand. There are varying levels of how much you can use it for sash work. If I had enough multiples, I'd spend the extra several hours programming it would take to completely do it all on the machine. I'm talking about using tools that have an offset double profile, one of which gets cut off and reclaimed to be used as stop - it takes not much more time to actually draw in and cut the miters on those stops while I'm zoomed in on the screen and concentrating on it. Stops fit perfect and tight without the guys hand fitting tiny pieces with a chopsaw and disk sander. A less intense approach is to just cut out the TDL bars as s4s with a straight bit. You end up manually machining from here on, but knowing all your angles and sizes will fit.

It took me some time to have faith in it, and gradually new ways to do things became apparent. The ability to carve away at gnarly end grain profiles and copes helps too. Clean and smooth, little or no hand sanding. Sure you could do the same with a shaper, but too much time gets wasted moving a perfectly set up fence in and out all the time. Dangerous work, like profiling tiny bars, or raising small weird shaped panels can be done standing back watching, with a feed control rheostat remote in your hand.