Question

Is anyone making laminated beams out of side lumber? I heard of this idea in a Cooks Saw magazine and it may help in some of my building projects. My mill only cuts 16 foot logs and here in NE Oklahoma, our logs are really tapered if longer than that. Can the beams be made without planing each board? How dry do the boards need to be? I will be using red oak or post oak, so how strong will it be?

Forum Responses

(Sawing and Drying Forum)

From contributor M:

These beams you want to make do not meet building code requirements unless they are used for non-structural capacity. I can not understand how these could be made without holding something up. Owning two mills and being a build code official, I tell everyone that wants to use ungraded lumber that it is not worth the hassle. Wood being as cheap as it is now because of market conditions, why would you want to do this? I love to cut wood as much as the next guy, but I would not use my own lumber in a building for support because of the liability involved. Who wants to be sued if someone gets hurt or killed? There are manufacturers that are certified to build glue-lam beams, even radius beams. You and I are not. The wood has to be prepared correctly, and the proper glue must be used. Then the wood is compressed to a certain value until the glue is dried. I know how to make them, but I still would not.

I am not saying that you should not do this; I want to remind everyone that there are consequences for things we do so that no one gets hurt. The whole county uses the same building code; some areas do not enforce it, though.

I think there might be a show called “How It’s Made” that has the answer you’re looking for. It is on the web from the Science Channel.

The beams are computer designed to develop the needed strength. The design also indicates where wood is not needed... extra wood adds to the weight and actually reduces the strength. As an illustration, which is stronger and stiffer, a 2x6 loaded flatwise or edgewise? So which width and depth is best for a beam?

In this case, the building codes are designed to assure safety of the occupants. For log homes are similar structures, there are regulations to assure safety. These regulations are conservative to assure virtually 100% safety in all sorts of conditions.

In this case, by side lumber, does this mean jacket boards? Certainly the species is important as well. The log size is also important as with small logs, there would be knots, tension wood, etc., all items that reduce the strength. The pieces must be dry before gluing, as glue does not hold well with wet lumber and also the drying stresses for a wetter piece would weaken and even break the glue joint. Certainly, oak is strong, but it is also heavy, so beams of oak often do not have a lot of excess carrying capacity.

Contributor A has great comments that indicate how important safety is. Remember that you may be willing to live in a structure that is below the safety standards (below code), but eventually you will sell this structure to another person and that person deserves safety.

The bottom line is that you cannot make your own beams out of ungraded, incorrect MC, unplaned lumber and have them perform safely and adhere to the established safety standards for a dwelling.

But I disagree with the premise that any and all timbers or glu-lam produced by any or all individual sawyers would be categorically unsuitable for use as structural timbers. While it is wise to err on the side of caution, I think we live in a day where blanket statements tend to form a mindset that says we as individuals should just leave all the critical thinking to large corporations and avoid any risks in life whatsoever.

Would I cut timbers or sell site-built glu-lams to a contractor who is building a doctor's office? No I would not. Would I cut them or sell them to him for his hunting lodge? Almost certainly, provided I had suitable grade logs that would produce clear wood, and he was willing to wait.

There's an element of risk involved in everything we do. We should always weigh the reward versus the risk, and make our best decisions based on that. While I believe there are some sawyers who probably have no business even cutting cribbing, I think there are many more who produce quality, sound timbers for structural use every bit as good as something bearing a stamp. Of course the issue of whether or not they are sold in a code-enforced area is a whole other discussion.

I disagree with the premise that it's a patently bad undertaking for any sawyer to produce structural timbers for any reason, or even make their own glu-lams, if this is in fact the notion being put forth.

In order to develop a strong glue joint, the pieces of wood being joined must be extremely close to each other (0.006"). This would involve a great number of clamps; further, handling and applying the glue would be critical. In the years I have been in this business, I do not recall many small and medium size hardwood sawmills that would also have the expertise, room, equipment to make laminated beams. They certainly could make sawn beams that would then be evaluated for strength, but laminated is not possible in most (maybe all) small or medium sized mills.

Quiz: If you have different grades of lumber for a laminated beam, where should the two strongest pieces be placed - top, bottom, middle, or ?? Is there, when installing a straight beam such as a header over a door, a face that is the top, or can it be installed in either direction? Is 1:6 slope of grain too much for a structural piece?

I do own some buildings that my grandfather built in the thirties that have stood the test of time, some of which have 8 inch poles over 20' long for door headers .some still have the bark on them and I don't think they have a grade stamp on them, and they are safe.

There is no question that beams (ungraded) can be made and serve well, and they were often so in the past. Some were indeed nail laminated. I do think that grandpa had much more clear lumber and larger trees than we do, so he had a better chance of making a strong beam.

Note that hardwoods can be graded for structural use.

Just a few weeks ago I bought 180 pre-cut studs and paid $2.55 each for them. The customer did not want the studs of his home to bow so he said my studs would not work. Of the 180 studs, I culled 13 of them as below grade and not fit for use. Had to take them back to the store and exchange them and they wanted a 20% restocking fee. I asked why a restocking fee, as the boards were clearly not good boards? Most builders would have used them and the house would have passed inspection since the boards did have a grade stamp.

There are many old barns and homes here with no grade stamped lumber in them at all. (Most old homes, including the White House, are that way.) Common sense is not so common anymore.

In my area, ungraded lumber is used everywhere. The local authority asks the builder to strengthen the building by one size. Not a bad deal since the building codes should be considered the minimum allowed requirement. If an engineer is running design calculation, the rough sawn lumber can be used with no changes to size.

I would be happy to grade my own lumber. It absolutely makes no business sense for me to pay a grader to do this because I have many small jobs that typically need a quick turn-around. We tend to cut larger logs than the stud mills, and in doing so it is easy to exceed their quality. A grader's got to eat too, just the nature of the business.

As far as how things use to be, those good old days are gone. Although there are a lot of nice old structures standing, there are a heck of a lot more that have crumbled because of the very components they where built from.

“R502.1 Identification. Load-bearing dimension lumber for joists, beams and girders shall be identified by a grade mark of a lumber grading or inspection agency that has been approved by an accredited body that complies with DOC PS20. In lieu of a grade mark, a certificate of inspection issued by a lumber grading or inspection agency meeting the requirements of this section shall be accepted.”

This paragraph appears in many places in the IRC and IBC. This building code has been adopted by many countries around the world including every state in the US. Every jurisdiction that adopts the IRC and IBC can choose to be more restrictive, but can not loosen the code. Some jurisdictions choose to look the other way and let people do whatever they want.

I will agree that many older buildings are still standing after more than 100 years, but almost everyone has walls bowing, floors and roofs sagging. The reason for this is most supporting members were not sized correctly. I watch episodes of “This Old House” where they have to repair deficient load bearing members in every project they do. What is up with that? If our forefathers and mothers were so great in building, why is this happening?

Those of you that think that your sawn wood is superior to what you can buy, prove it! I know the wood I cut is far better than what you can buy in the stores. Can I prove it? No. I do have a structural engineering background and can calculate the strength of the members. Do I have an engineers stamp? No. If you can get a structural engineer to stamp your plans with the use of rough sawn wood, the jurisdiction almost has to accept this. The engineer also must provide a final report that states that his/her butt is taking responsibility for the safety of the structure. You will not find many that will do this.

I also disagree that someone must be "crazy" to sell framing lumber if he so chooses. I would agree that he may be crazy to do so without first understanding how to structure his business so that asset attachment is limited to the bare bones of his business, and not his entire castle.

Bottom line is yes, the little guy continues to get squeezed out of every market which could be profitable because large corporations don't want the competition, and governments no longer represent the little guy. They kneel at the altar of big-moneyed lobbyists. Any little guy who wants to sell where he can regardless of how smart or stupid it may be, does so knowing the risks, or else he'll find out the hard way.

I stay out of all those markets and limit my products to woodworkers, turners, and niche markets. I also would not knowingly sell to hobby toy makers who resell their products at flea markets. They are all breaking the law now too, and are subject to outrageous fines and litigation. Sawmill operating permits are not far down the road. I'm not kidding.

In the past decades, we have changed our living structures... added increased weight to the structure (king's size beds, books, pianos, entertainment centers, big refrigerators), added upstairs laundry rooms, added longer open spans, added less tolerance of bouncy floors, wavy walls, and wavy roofs, and so on with less desire to build a new structure (log cabins were considered somewhat temporary, for example). Further, we insure them against fire, wind, rain, snow, etc., which means that the insurance companies want a reasonable level of construction, even for outbuildings that may house insured animals, cars, etc. In short, it is hard to compare grandpa's buildings to today's.

I believe it is necessary to raise an issue while working on a solution. Raising too many before the work begins is not productive. We should be working together to become part of the standards, and if that is grading/testing/processing lumber, then so be it! This forum should help make this happen... What an opportunity!

On another forum I found a reference to a class for grading softwood. The cost was said to be $700. The class part was okay, but becoming certified is still challenging due to the need to take other steps, not to mention the fees.

Could you direct me to the U.S. Code or that part of the U.S. Constitution that strips the States' sovereign rights to enact laws by legislative act and gives a private entity the powers to override a states' ability to do so?

I don't recall studying it in any of my law classes. Then again I don't own the largest sawmill in Washington State, so I could be wrong.

Contributor A mentions IRC and IBC standards along with 100 year old buildings with sags and bows. It's obvious you haven't seen the lack of quality being produced today and our codes allowing 7/16" CDX (junk) on the roofs with all the waves and sags after 6 years. I do agree we need codes and guidelines, but correctly used, not abused.

Gene's comment is correct that our weights and spans have changed over the years. And as a new sawyer, I agree with contributor T that we can produce as high or higher quality as the large mills, we just don't get the grade stamp.

To the original questioner: Lamination of some sort has been around for centuries! Even timber framing's scarf joint is the layering of one or more. I've seen in multiple old structures the laminating of green ungraded lumber to create beams and trusses that have withstood the tests of time.

The bottom line is, from 25 years of experience studying and repairing older structures - sheds, barns, residences, churches and courthouses - is we have the same building issues now as they did hundreds of years ago. Some value building safely and correctly, and others choose to cut corners. If this wasn't true, there would be no need for codes or even law enforcement.

I had a great, great uncle that worked for the railroad designing and installing timber trestles. After many years of good designs and no failures, the railroad decided that he was going to be removed from engineering because he didn't have a college degree. He only had a third grade education. His degreed coworker, who already had many bridge failures, replaced him. The sad conclusion is our world is revolving more around degrees and grade stamps, and not around good morals and quality that can be produced by the little guys.

The codes are adopted at the state level first, and then the county, city or town level depends on where you live. I live outside the city, so I am governed by the county. I work for two cities and they have to use the state amendments and then add their own, if they are more restrictive.

Here is an example. One city I work for has the most restrictive rules on height requirements I have ever seen. The other city could almost care less. This is all within reason. The city that has the very strict height requirements is because of views of the Seattle skyline. The structure, when done, must have a licensed surveyor state what the height of the building is, and stamp it with his stamp. If the structure is too high, it gets torn down, or repaired to the level that was approved when the plans were submitted. Do I agree with this? No way! I do what the city council directs me to do. This is what happens when rich people run amuck. You do have to understand that the average price of a home in this city is about $8-900,000, with many well over 5 million.

Someone brought up the 7/16 OSB on the roofs. Back in the 70’s and 80’s this was only 3/8 CDX with very poor ventilation. The 7/16 OSB is a step up from the 3/8. I personally like the OSB because it uses smaller trees, and saves the old growth forests. 7/16 OSB works great here with proper ventilation and the ventilation is the key to it lasting. This does not work with high snow loads or with high year round humidity.

I grade by their handbook (try to get one of those as well). The DOC PS 20 was to ensure that with interstate commerce we would all be talking about the same thing. So a 2x4 was the same in NY as in AR. Not so some big mills could get together and exclude the smaller ones. The standards were so that when you bought lumber, we were all talking about the same thing in terms that were defined.

It is no hard feat to become a Hardwood inspector. I went to a large softwood mill one time and the boards were going by the inspectors at a rate of 3 per second. It took a major flaw to get culled. I am putting in a picture of two of the boards that made my load and both have grade stamps. Neither board would have left my yard to be sold as a stud. My boards did come from Canada.

In Arkansas if you pass the test (open book) for Contractors License, most of it is on Workers Comp law and really has nothing to do with knowing how to build. Most Civil Engineers who approve your plans could not build a house. I studied CE for 3 years before I took off sawing. Yes, they are needed and do provide a great service. Yes, there needs to be a way for small mills to grade and stamp their lumber and have no more liability than the larger mills seem to have.

Remember that 20% is allowed to be below grade. Just because it has a stamp does not mean it is worth using.

And although I use quotes for the problem/solution nexus, I don't mean to trivialize them. They are important issues. But they have, like all political impetus, been used as tools to concentrate control into the hands of a few. Just like the American farmer, on a much smaller scale, the individual American sawyer cannot afford to send a lobbyist to DC to buy a congressman.

I know this topic is not something most sawyers come here to discuss, but the fact is, the aforementioned issues have taken a back seat to the real motivation behind most of the regulations that slide through on the coattails of other bills, and that motivation is to eventually completely squeeze out the small guys.

I would be happy if a grader could be available for a reasonable price relative to the work my mill can do and my customer needs. I have checked - it would nearly double my selling price!

If you price an inspector, they get travel pay, then so much to inspect. You would end up making your lumber cost more than what you can go buy it for.

I do agree that hiring a grader is expensive, but combining several mills together can often prove a better option. But the large mills can make lumber quite cheaply, so it is hard to compete in this commodity market. Hence, niche markets, and other non-commodity markets are better options.

Incidentally, I am old enough to remember when you went to a lumberyard and the construction lumber varied in size by quite a bit... before the present standards were in place.

I grade my lumber by the book and stamp it with my stamp. It is far better lumber than I get at the store. Sometimes I do not produce enough to meet my own demand. Lumber like flooring and siding does not have to have a grade stamp. Since my repeat sales are so high in the average of my annual sales, it must be good enough and some of my products are higher in cost than the store.

There is absolutely no reason that each state could not adopt the grading guidelines set forth by DOC PS20 and NIST, under their weights and measure codes/statutes and if necessary require a bond for stamp grading of construction lumber instead of allowing a monopoly to prevail in such a manner.

1) DOC PS 20, Sec 2 TERMINOLOGY

ss 2.1 Accreditation--Procedure by which an authoritative body gives formal recognition that a body or person is competent to carry out specific tasks.

(they have no standard procedure)

Until 1999 I was a successful remodeler employing eleven headaches. I hated using the spruce and pine crap I was forced to use. I would have gladly paid more for better lumber if it were available. I served a high end market and did not advertise, but had a constant backlog of work. I produced quality results. I had to go through a lot of lumber to do it. There are a lot of builders and remodeling concerns that would jump at the chance to buy the kind of quality lumber others can produce, but it is simply not available to them without the caveats because of politics.

I see a 2-dimensional attitude here and it's because some people have become so conditioned to just accept the status quo, that they have *become* the status quo. Gene, when you say that large corporations can produce studs so much more efficiently than a small sawyer operation, you are correct, but you miss the point so dramatically it makes me wonder what you do all day. Small sawyers on the whole do not want the ability to compete with Weyerhauser. They just want to go after the target markets they choose. Like upscale builders who will pay more for quality lumber. But the Weyerhausers of the world see that as too much competition and make sure the whores in DC write the rules that prevent that competition.

The spec builder and tract-home builders are not what the contributor A's of the world are after, necessarily. They want to be able to sell to the guys like themselves who produce quality over quantity, like the remodeling business that put my family in high cotton eventually. I didn't do it by using junk materials. My bid was usually the highest or close to it, but I had the reputation to sell that kind of product.

Independent sawyers should be allowed an affordable avenue for reaching those markets simply by a lack of oppressive regulations. Just an affordable means to bring their quality products to market, and if they cannot meet the "stringent standards" of the Weyerhausers, then they can flip pancakes at IHOP.

It is possible to hire a part time grader for softwoods. It does cost money for the grader's time and their continual training, inspection, etc., which even the large mills have to pay.

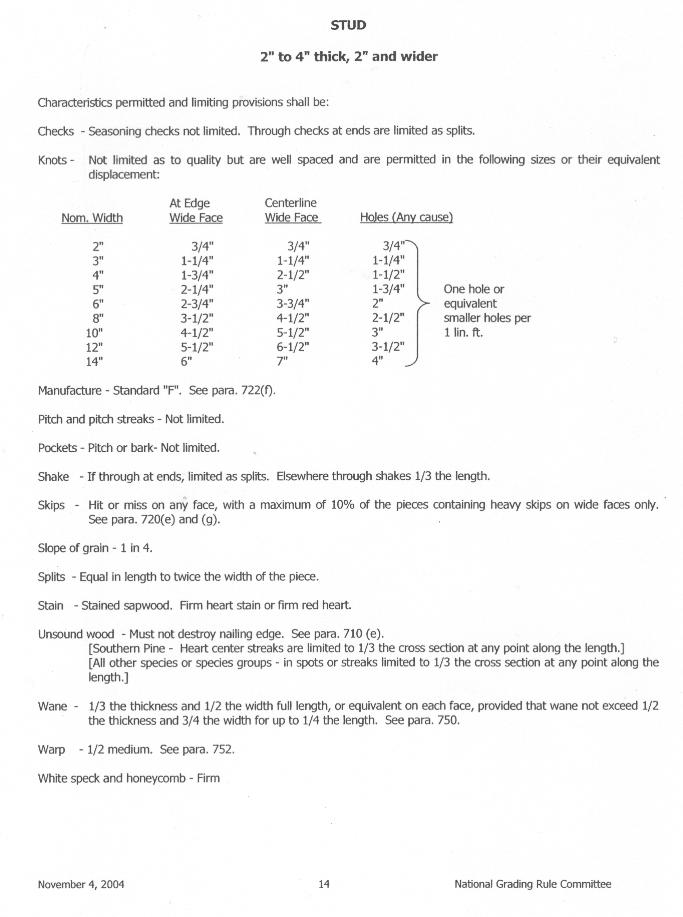

Note that the grade of STUD requires exceptional straightness (for 2x4 by 8 feet, 0.25" crook, .375" twist and .75" bow), nailing edges must be consistent, and so on. Of course, this quality is at the time of grading and is continually checked by the grading associations both here and in Canada. They cannot guarantee that the buyer will ship and store the wood correctly; poor storage can lead to warp and in fact it has been documented many times that storage before sale is a big issue. Should the lumber be below grade, every piece will have a mill number and a grading association name so one can file a complaint and such complaints are indeed handled fairly.

Of course, there are better grades than STUD; these grades provide higher stress ratings. In fact, it is not uncommon to find that other products in addition to 2x4s will be machine stress rated rather than visually graded to assure even more precise strength and stiffness ratings.

When building with construction lumber in the South using Southern pine, the main grade used (other than 2x4 studs) is No.2. Over half of such lumber is also pressure treated. When one mentions higher quality, does that mean stronger, stiffer or straighter?

A floor joist or truss is designed based on strength and stiffness; almost always, the stiffness is the governing factor. There is more than sufficient strength, maybe 2 to 3 times more. So, what does higher quality mean? Does it look better? Is it straighter? If straightness is the issue, most likely the shipping and storage people are mishandling the lumber.

Although I was employed by Virginia Tech and the University of Wisconsin, my job involved providing technical assistance to mills, manufacturers and builders, visiting hundreds of mills every year for 30+ years. These were both small and large mills; hardwoods and softwoods. I conducted seminars for builders on grades, products, installation (such as nailing patterns). I have managed a sawmill. I have built buildings; in fact, right now I am building (nailing, screwing, cutting, etc.) a large building (wood frame with metal siding) in NW Iowa. I do believe that I have seen the practical side of sawmilling in more mills (small to large) and in more difficult situations than most other people... Mills called me in when they had problems.

Don't forget that stud mills accept 5" logs and somehow get two studs from that. I suppose they accurately make a stud that includes a lot of natural edge. That is one of the eye popping reasons that we say we cut to a higher quality. The other is strength - it is not difficult to witness the increased strength in a rough sawn board. I haven't produced a mechanical performance test to show these strongly held beliefs. If we can get some help with standards I am sure it will come to that.

We can all see how important the standards are and we want to be part of that. I have suggested a new standard for rough sawn that matches the design standards for dimensional lumber. They would be different products but could be used in the same construction designs.

The large mills in BC's interior, I'm told, can process logs for $100 per thousand. That includes unloading the log truck, debarking, milling, kilning, planing, grading, packaging, and loading the finished product. That's at a rate of up to 1,500,000 bft per shift. But they can't do custom orders.

Studs coming from small diameter logs is actually a byproduct of modern forestry practices and is an important part of good stewardship. The days of heading into the woods and felling the monster trees because of high yield and everything else knocked down and left to rot are gone. The U.S. lumber companies, at least those that are left, have invested heavily in technology that allows them to utilize this second, third, or even fourth growth timber and turn it into a viable product.

The Southern pine mills can produce around 30 billion BF annually; they are down because of the poor economy now. I do not think that they will worry about small mills greatly affecting their markets. Canadian mills provide even more lumber annually.

It is well to remember that these mills are producing large quantities (and about 82% of their cost is the log), so they need to make only a small profit on each stick of lumber. If a small mill were to produce lumber with this same profit margin per stick, it could not operate. Hence, niche markets are so much more attractive. In fact, these customized markets are not of interest to the large mills.

A consumer can buy No.2 2x4s, No.1 2x4s, and STUD 2x4s. Actually, a STUD is straighter and has a better nailing surface (see my previous note for the actual straightness) than the two higher, more expensive grades. I am doubtful that a small mill can make a better stud unless they use more expensive logs and more expensive kiln drying, the cost of which will destroy profits.

In the South, a consumer can buy 2x6 through 2x12 No.2, No.2 Dense, No.1 and No.1 Dense. So, higher quality is available at a higher cost, but the builders do not buy it. The higher grades go almost totally to truss mills that can afford the cost.

Large mills are very aware of the cost of production, the benefit in improved production, profits and so on. In a commodity market, the competition will try to reduce costs to make a sale, as one can buy the same product from many mills, so the lowest sale cost is the one that wins. (If you visit a medium or large mill, you will see the excellent quality that they produce; it will be better than what you have in the large lumber stores where the product has been mishandled.)

I think that if small mills want to sell softwood construction lumber, we will need some way to assure that they conform to the size, strength, warp, and MC rules. We will have to check them from time to time (once a month and they will have to pay for the cost of this checking) to assure they are being honest and correctly indicating the grade. I think the cheapest way to do this is for a mill to hire a certified grader to come to their mill from time to time to grade their lumber. The cost of this grader would be less than the cost of any other reasonable options I can think of.

Every so often, a sawmill produces inferior lumber and grade stamps it using a counterfeit stamp. As they do not have to pay the grading costs, their product is cheap and a store might buy their wood unknowingly... In a commodity market, the cheapest price is what they buy. Likewise, from time to time a regular mill will produce incorrectly graded lumber and will not correct their grading, so their stamp is revoked. This counterfeit stamping happens more often than one thinks.

I had the private capital to do it and the timberland as well, and back then the market warranted, and fuel costs were not so prohibitive that I could have trucked my products the 120 miles to the nearest buyer. I had been given - yes, given - several hundred acres of loblolly pine with every species of east Texas hardwoods that grow here. For a newbie greenhorn with water behind his ears, *free* timber, and zero interest venture loans, it looked like a no-brainer.

Knowing what I know now, it's easy to see how I would've fallen flat on my face with the sudden fuel cost spike, falling markets, and who knows what else. Even under the best of circumstances it would have been touch and go.

I don't disagree with anything you said in your last post, Gene. In fact I learned a lot. Especially about counterfeit stamps. The thing I have a problem with is how the small mills are blocked out of their local markets, not just by the market factors you (accurately) describe, but because they have to compete with the mega corporations and their lobbyists when they are not even trying to get into Home Depot in the first place.

I'm not for any kind of federal government intervention, not even in the form of regulations favorable to the small sawyer, or subsidies. I hate them for big business so I would hate them for small business.

But I believe strongly that small mills ought to have access to their local markets. I believe individual state legislatures ought to write their own laws that allow a sawyer to have access to a state-sponsored monthly stamp program for a nominal fee. I don't believe anyone and everyone who owns a mill should have access to it. I think it ought to be regulated just like HVAC, plumbing, electricians and most other trades, so as not to be a haven for dishonorable types who bilk the public and create unsafe conditions in their wake.

The program I see is one where a sawyer wannabe has to pass a test, just like the electrician's exam I had to pass, and must do at least 2 hours of CE each year (2 hours is nothing). A sawyer who passed the requirements would be issued a license to sell whatever lumber his license stated (there are different levels of HVAC, for example, and the "B" license cannot sell or service certain types of systems). His lumber would be graded monthly and if he received a large order and wanted to sell some lumber before the next scheduled visit by the state grading agent, he could schedule a visit out of his pocket. The lumber would only be allowed to be sold and used in that state or states with reciprocal agreements. That's no big deal either, because those kinds of laws are on the books for everything you can imagine anyway, and many things you cannot.

I can hear some of you saying "but that's not going to change the fact that people aren't going to buy construction grade from small mills when they can buy it much cheaper from big orange." I guess that's where I am probably living in a fantasy world, because I know from experience that a small mill *can* compete with the Depots even in the construction lumber market in many ways. I'm not saying a small mill can make a million a year, but with a feasible stamping program, a small mill could sell enough to provide a good living for his family if he did everything else right.

There may not be many guys like me out there who have access to timber at little or no cost, but even considering the cost of logs, if a small mill had access to an affordable and regular stamping program, it would open the door for many small mills to to sell lumber locally that otherwise could not.

It would take a serious effort by a few individuals at first in a state where it has the best chance to come to fruition, and that state would have to be one where logging was almost non existent, because the logging lobby would squash it like a bug in Washington State or the like. I realize this sounds like a pipe dream, but maybe I'm still green enough to dream.

Small mills simply cannot compete with millions of dollars of capital and dozens or hundreds of employees for the same market. But they *can* sell the same kind of products and do so profitably, in my opinion. Doing it legally could be a whole bunch easier with fair access to those markets.

Agreed, yet with hardwood, we smaller mills are not limited or frozen out of the market by a regulation that affords a selective few a monopoly on a specific commodity market. We are allowed to market our lumber as meeting the standard grades as outlined in the NHLA rules without being forced to join some group or pay an additional fee to a private entity for the use of the rules.

Another part of any market is the distribution chain, wherein every link in the chain has to place a markup on the commodity in order to make a profit or at least cover overhead. If small mills were afforded the opportunity to grade their lumber, without having to pay a $500 a day fee plus expenses to hire a transient inspector (from the SPIB for example), and they can't compete, then the laws of natural selection will prevail. But to simply lock them out by excessive fees because some totalitarian group wants to control the market, is wrong.

I assure you that I and others could cut, dry, and market studs, pursuant to the grade rules, and make a livable profit at the $2.55 price tag that was mentioned above (or whatever the current market price is). Yet, if we had to have those same studs graded by a transient grader, we would have to add a minimum of $2.78 per stud to recover our grading expenses (in his example).

It has been some time since I had softwoods graded by the SPIB, but if I remember correctly, there was a bf limit that could be graded in a day without incurring additional fees. Further, the savings that would be gained by having an inspector grade several mills at once would be minimal and would be offset by the additional time wasted arranging a combined grading session. Further, they will only grade lumber for you that was produced by you.

"I think that if small mills want to sell softwood construction lumber, we need some way to assure that they conform to the size, strength, warp, and MC rules."

The market or the laws of natural selection will help ensure accountability. And I do believe that this could be handled at the state level. I'm sure any state's DPR or DOA could come up with a fairly simple procedure to protect the public much better than what is being done now while allowing a free market to prevail.

Basically my argument is, the way the system is set up, it is a suppression of one's rights to prosper, without unfair government intrusion. The federal government has given a selected group the ability to control a specific market and denied the people's right to compete freely.

How much someone does or doesn't spend in order to get into the market is irrelevant.

When grading hardwoods using the NHLA rules, we do not have a safety factor involved, so anyone can grade or learn to grade that wood. Further, hardwoods are not used as is but are almost always cut into smaller pieces to achieve the desired quality.

The earlier post that said no lumber should be used in framing construction that isn't graded and stamped is very offensive to me. I have cut a lot of lumber that is stronger than store bought stamped pine. I have also cut some that is junk. That stuff turns into firewood instead of being a percentage that gets by.

I do some custom sawing now. I used to raise chickens on contract, but the economic slump made my contract contract, and I don't raise chickens anymore. I do have a lot of storage and my mill is set up in an old chicken house - it works out pretty well. I could only get 22 cents for my logs at a pallet mill 10 miles away. Now I get 30 cents plus 30 cents for sawing and people come to me. It's pretty good sometimes, but not always consistent. I just spent a week without a sawing job, but I have a couple orders for next week. I'm still optimistic that there is demand enough to support my small hardwood mill. I offer a product that Lowes doesn't - full 2 inch trailer floor boards that put up with cow manure or dozer tracks, or maybe exact size 1 piece beams or cants for flatbed semi trailers. Plus, they don't sell high quality firewood in bulk. And I do cut quite a bit of hobby wood.

Understood, but it is not a self regulating entity. It is more of a monopoly. Back in the day, a construction crew may have consisted of one to three people building a house from the ground up, and the quantities of housing that are being built, even in today's economy, were not built. Exponential population growth gave rise to the need for more housing and standards.

We also didn't have licensed contractors, framing contractors, roofing contractors, etc. that were held accountable for the construction of dwellings like we do today. These people are licensed at the state or county level; they are not allowed to self govern at a federal level.

Since I see so many bad boards with stamps, I will say the system is not working. They do not police themselves very well. I do realize that most builders cut them into shorter pieces so that they are not wasted. (There are many cripples in a house.)

There should be a State Level PS20 that allows small mills to sign up and have rules to follow just like the Weight and Measure guys do. They come check the scale.

I will never produce enough studs to hurt the big boys, but the truss company a few miles away would really like to buy 24' 2x6's to make trusses with. But without the SPIB logo on my stamp, they can not (or so they say). That's okay, as I need them anyway.

Even the SPIB states that grading lumber "cannot be considered an exact science." Since the rules allow for a few bad boards to come through, the system builders should know a good board and not use anything that is questionable. I would be willing to guess that very few buildings have failed because of poor sawmill lumber. Design, foundation, and over loading are the major causes of failure. Most very old buildings were not built to last a long time, just to get people and stock in the dry as quick as possible. The fact that many have lasted is out done by the many more that were gone in the owner's lifetime.

As for laminated beams (glued up ones), most firefighters do not want to enter a burning building that have them. They fail at 300 degrees with no hint of going. They may stress test well, but time will tell all things.

I will give up my stamp when they pry it from my hands.

When talk of rough lumber circulates, is this for the purpose of home construction, and would it be the same dimensions as standard framing material? I would speculate non-typical studs would be a nightmare, being that so many other construction products are based on a typical stud spacing and thickness.

When we build homes, sometimes we use boards machined to specs. Sometimes we build with 1 5/8 by full width boards or timbers, since in this area getting replacement boards should never be a problem.

The home in the photo was built mostly with lumber sawn from the owner's land. He did not buy much other stuff to finish the home, and most of it was sawn by me from logs bought.

I missed the phone call from the ALSC folks today. I was producing some structural parts for a customer. The kind of parts that would fit into this product category. I hope you are starting to see that these are important products for myself and many others like me.

That was a very nice pictures contributor A posted (though not sure about that back door - the step looks like a big one).

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Here in the Ozarks board and batten siding is very common even on very expensive homes. I have done it on the gable ends of log homes that cost close to $1million. Siding and flooring do not need a grade stamp. I am not offended.

Where I live, if I wanted to use my own lumber without it being graded, it would never pass the first floor framing inspection. We could get a traveling inspector to grade lumber, but it is not economically feasible with lumber prices so cheap now. Our cost of living here is extremely expensive, which is the reason I charge as much as I do. For me to cut wood for someone’s house would cost two to three times what it would cost to just go out and buy the wood, which includes having the grading inspector inspect the framing members. I do not get many people wanting framing lumber because they know how strict the code is enforced here. The biggest problem I have had is with transplant people from the east and mid-west where many people use their own lumber and sawing prices are inexpensive. 25 to 30 cents a board foot are way out of line here.

When I started cutting wood in 2001, I charged $300 per thousand. That lasted less than a year. After that it was $75.00 per hour until 2007 when it was raised to $100.00 per hour. When I work as a building inspector, I make $32.00 an hour without benefits. There is just not a call for structural wood here, since most of our wood comes from Canada and is very cheap. I sell a little wood on the side, but buying logs, cutting them and selling the lumber would never be possible here. I have read many posts about cutting RR ties, which does not happen here because all ties are changed out with concrete ties for the long life. Wood ties just do not last long. Labor must be cheap back there to keep replacing ties all the time. Do not be surprised within the next few years if wood ties go away forever, with the environmental issues of creosote.

Most of the wood in a house does not have to be stamped. Local inspectors take my stamp as just fine. Most comment on the lumber and the way that I build, then sign off.

Here they are removing the concrete ties and replacing them with wood. Seems the vibration and temp changes cause them to break. Cooked oak ties last 10 plus years, then can be resold for landscape timbers.

You will not have to worry about me being transplanted there. We may be poor as church mice and backwards in some ways, but the living is good here. Now if it would just stop raining.

Even though contributor M and I live only about 80 miles apart, we present a different point of view on this subject. I live in a rural area; there are a lot of folks that have land, hence the need to use the resources they have - they are thinking green. I hope to get over to his place some time and see his equipment. I know he has done some very interesting upgrades. Our prices look about the same.

Here is a picture of the timber frame front porch that I cut for my customer. I cut all the boards you see in the picture. It came out beautiful. Contributor A, your timber frame would sell for at least three times your price here!

The original question has brought up some interesting discussion. If we humble ourselves we can see life can be simple and still built great. We've seen various opinions on building, materials specs and rules & reg's/codes, how different areas have other ideas concerning "what's politically correct" or not.

I live and make my living in a rural area. Just because we don't have degrees and strict codes doesn't make us wrong - we can still build safe, beautiful houses. Does our area have unsafe builders? YES! But so do the heavily coded and inspected areas. Percentages are roughly the same, just their numbers are larger.

Let's all remember to love what we do, and strive for safety and quality. Every regionhas different conditions (weather, seismic, soil, flat ground, hillside) to consider as what might be the reason we build and see things differently.

Another gem of wisdom that I heard years ago from engineering sources was that most structures that are not professionally engineered are overbuilt. An engineer could have built the same thing using much less material, at a lower cost. So less steel/wood/etc. to get the job done. But most of us have seen over-engineered structures that, while they did the job, would break too easily when they were pushed too hard in unexpected ways. I tend to like more forgiveness in everything I use. That way when I screw up they won't break.

Second, I have never seen a short course on grading softwood construction lumber offered, although years ago I did teach edgermen about producing the highest softwood grades, and so we taught them about the grading requirements. Today, with computers, such a class is no longer given. But a one day class on softwood grading would be interesting for sure. Can you give me more info about this class, such as past or future locations?

Third, why would an inspector want to know the dryness or scale? It is my understanding that nominal size, species and grade are all that is required to make a strength decision.

And what sort of test do the attendees at a one-day short course have to take to make sure that they have the softwood construction grading rules correct?

Most of the materials used in homes here have to be graded, from framing to sub-flooring and wood shingles, etc. However, it provides a niche service for a planing mill that grades and dresses lumber, perhaps something that would work in the various areas in which you operate.

Perhaps I have a different take because in Canada, most of our products are exported, therefore graded and stamped to provide a basis for pricing. In the U.S. 75% of the products produced are consumed within the U.S., allowing for homegrown markets. However, the lower U.S. dollar for the near short term may provide markets globally, which will require grading standards.

I am a building contractor with a sawmill. I have to carry numerous licenses and one which I plan to add is the Ontario Lumber Manufacturers Association (OLMA), a recognized stamp in the U.S. It requires a 3 day course and exam and an annual fee based on production, and my mill would be licensed. I could grade both dressed and rough cut lumber.

As has been mentioned, the grade and size specifications are at the time of grading.

Doesn't the license also include unannounced inspections by the association, perhaps as often as once a month? Are these part of the annual fee or are these an additional expense? Will you be licensed to stamp just a few grades of 2x lumber or will the 3-day class include 4/4 as well, many different grades and heavy timbers?

I would add that the OLMA has always been rather progressive and high class in training. It is a good choice for membership and training. The Maritimes also have an excellent association.

The alternative materials section would allow an inspector to accept native lumber, but it allows them to require third party inspection and most aren't going to stick their neck out. I have offered to proof load and they would rather have a grade stamp for the file. If you are a contractor in my state and fraudulently stamp lumber, you can kiss your license goodbye.

NH has a native lumber law. Google it, it's not bad. NY has something similar. In NC I could use lumber from off the property in a home. In VA I can use it for agricultural use only, without a stamp from an accredited agency. I checked a few weeks ago - bringing in a TP grader for me right now is $85/hr, half day minimum including windshield time. The half day minimum is drive time, in my case.

I have been trained at TP and they would be happy for my little stationary mill to join and get a stamp, but I can't swing it. I've been trying to think of some way that would be fair to both sides and the best I can come up with is to have land grant universities train future forestry and engineering grads by having them come out to small mills and perform the oversight service that the grading agencies do, after the sawyer is trained.

Another thought is that somewhere in the mandate the ALSC is not supposed to favor or unduly burden... I'd say it does that to small operations, so maybe they should be required to provide the service for the same BF price they do for the big boys, instead of hourly. This is not a large market and I doubt there are that many calls per month. The pool bears the cost... part of meeting the intent of the law. They are abusing small operators now; this is outside of their mandate.

This is not just an issue related to dimensional lumber, but to any structural wood. Logs and timbers don't compete with the big box. I'm not competing with a commodity but also don't feel I should be penalized just for being a small enterprise.

I've rolled through packs of really ugly lumber to find that the grader was hugging the line, but I agreed with almost all of his calls. That means the lumber is as strong as the plans specify. The allowable percentage deviation isn't intended to allow junk through, but to allow for variation in opinion in a natural product. No lumber should break below allowable design strength for the grade, which is what grading is for. A true #2 is not an especially pretty stick of lumber. That said, I did go to the big box during grader training and brought some sticks to class that failed to meet grade.

Owning a grade book without being trained to use it is akin to trying to write a novel by reading a dictionary. It can be done by some, but not many. If sawyers were training and lined up saying "we're trained, ready and being denied," it would be one thing, but that isn't the situation.

To me it looks like there's blame enough to go around. If we want the rules changed I think we need to show that we're up to it. Get training in place or avail ourselves of what's there, get trained, prove we can grade, then change the rules. Or alternatively petition our representatives to force the ALSC to mandate that all grading is by the foot, level the playing field, everyone pays into the cost pool. For the masses, the price of lumber just went up.

Therefore, in theory, we could develop our own process and rule to follow. Then we would need to convince the ALS committee to certify our grading process, and we would be in business.

In talking to Carl of the ALS committee, I found that a rough sawn lumber standard has been written. He thought that we should be able to find a grading entity to develop a solution for us. I will be checking his idea out this week (even though this is the snag many of use have run into before).

The same thing happens in wood grading. Thus an allowance of 5% deviation dictates 5% below grade pieces of wood. Thus, if I build an entire house out of the 5%, it will meet building code because it has the grade stamp.

What happens is, if a board falls below the grade stamped on it, the board is still used because the liability is passed on to the grading agency. "Not my fault, man!" So basically, spec homes are built with 5% of the lumber below grade but they don't fail inspection. I'm sure a lot of below grade boards are cut to smaller pieces and not used as manufactured. But aren't those cut boards still below grade? And where is the grade stamp?

Some sort of standard is needed. It is nice to have a 2 x 4 a standard size from Maine to California (but what if I want to build my house out of 2 x 4 oak?).

It seems to me that having a national grading standard allows end users to pass the responsibility of faulty wood products on to a third party. It allows mass production of houses and excludes the small sawmills in the process.

I'm not a grader by any means and like the idea of standards. If I were a grader I would grade toward the upper end and not the lower margin. Better too strong than have a failure.

Wisconsin Local Use Lumber Grading (PDF file)

I was looking up my notes and trying to figure out how to explain some of what grading is for. It might help to go into how the "allowable bending design value" for a piece of wood is derived. This is from an engineering short course at VT.

Consider a #1 SYP 2x4 with Fb=1850psi (Fb = maximum allowable fiberstress in bending)

The table value is derived from tests of actual lumber.

Average test value was 9,138 psi with a standard deviation of 3,205 psi

A 5% exclusion limit is used;

5% exclusion limit=avg-(1.645Xstd deviation)

9,138-(1.645X3,205)=3866 psi

Fb=(5% exclusion limit)/(1.6 load durationX1.3 safety factor on 5%)

Fb= 5%/2.1=3866/2.1=1841psi

This is from TP's grading class. 95% of wood in a pack should break at 2.1 times the allowable bending value or more. All wood should break above the allowable design value. See how they jibe?

As Dr. Wengert mentioned, this is not normally the limiting factor in design. Normally the modulus of elasticity, E, or stiffness, is the limiting factor. Generally a joist or rafter fails in design calculations in stiffness before it gets into trouble in bending. MOE is not a strength value but a measure of stiffness, a serviceability factor. People don't want bouncy floors or cracked tile or plaster. E is an average number, again from testing actual samples.

One very important item here is if you cut a 2x at a full 2 inches you add greatly to the strength of the member. Simpson book has a full page on rough cut hangers. I did contact them and they told me that they might not be available locally; the regional warehouse should have them in stock. It would take no more than a week to get the special order hangers. I really think this would be a great thing. I do see problems on training code officials on this. I have worked with a 20 year code official that could not tell the difference between Douglas fir and hemlock. To me this is very bad! (That is what is primarily used here on the west coast for construction). So, for us this would be easy; for code officials this would be more difficult.

Yes. This does not make sense. Centralized authority is out of control and this would be no different.

Contributor M does have the ability to accept ungraded native lumber now using the alternative materials section. He, or likely more correctly, his jurisdiction's attorney simply chooses not to due to the perceived liability risk. I would be curious if this is a real risk. The WI solution is requiring the inspector to allow an alternative method of grading, so I'm assuming they realize or perceive the risk to be minor.

If you are thinking the line graders are a superior breed to the folks gathered here, I'd like to offer something to think about. The class I was part of scored the highest of any grader training class ever. It was also the first time they had an experienced carpenter and sawyer there. This is not just a job to most of us here, it is what we are. The fellows in that class had never had a truss chord fail under a buddy's feet. A few stories during breaks helped them understand the seriousness of their profession. I tried very hard to take their job from something abstract and put faces on it.

My teammate in the grading class was a nice kid, recently graduated from college with a BA in business, had never worked in the wood industry. He was smart and conscientious, he'll come along fine. He left the class ready to begin riding along for his assignment as an auditing grader for the agency, overseeing the line graders. I left the class, went back to work and cannot legally grade.

I know you are probably one of the good ones, contributor M, you're here, but the system in place needs a whole lot of work. By wanting to require upsizing of each member, you are implying inferiority; I'm curious about your thoughts as to why. The graders I have talked to have pointed out that a small sawmill does not cherry pick the lumber. No lumber is below a #2 and no one is pulling out the appearance "prime," the #1 and the SS to sell to another market. The lumber from their experience is not inferior, it is vastly superior. It is #2 and better. At the building supply, increasingly I get straight #2; it is being cherry picked harder and harder by market forces. This is forcing very tight calls on the part of the line graders. By requiring special order hangers and the waste of material you would be again mandating a disadvantage to the small mills for no good reason. It also would make it more difficult to blend commodity lumber and native lumber in a structure. You still have the right to call for a grader or to reject material you deem to be deficient. A right you now have but probably have never exercised even when you have walked by poor materials. Does that mean I won't upsize? No, I happen to like 1-3/4" myself, 2 ply is 3.5" thick, but that should be my decision, not some random guesstimation by you. If it's on grade and correctly designed, respect it.

I am just a little hometown mill. The beauty of that is that I am held accountable in ways a company line grader in a faraway place never is. I also have more than 3 seconds to view all 4 faces and make the call. The hardest thing I found in the test was having to make the call in seconds: I can do it, but don't feel that pressure at home or on the job; things take as long as they take. I can stroll to the end of the board, think, turn it over a second or third time and then make decisions. The line grader is stuck at one end of a 16 foot stick trying to see the controlling defect on the far end. Those guys talked about things I hadn't considered, a day of rolling 2x12's every few seconds and having to make the calls. Do you reckon they glaze over occasionally?

Contributor M, I'm not really picking on you and I hope you don't feel that way; I'm picking on bad law. My father became a building official before retiring. I do pick on him.

Out of all the discussion on this post, it has been an eye opening experience on what code officials and jurisdictions allow in different parts of the country, even within my own state. I have been sawing for many years and when I went through college, I asked every code instructor what they would do if someone wanted to use rough cut lumber. I got pretty much the same answer from them all. Not allowed without grading! I have since learned, in the real world, that many jurisdictions are sticking their necks out, allowing rough cut lumber. I am not saying this is wrong; it just is very surprising to me after going through college and working in larger cities. This probably is because there has never been a lawsuit against them, where most code officials here have been in lawsuits and take a very conservative approach when applying the code.

You brought up cutting 2 x materials at the full 2 inches. I learned in a structural design class in college that a 2x4 cut a full 2 inches by 3-1/2 was 60% stronger than the standard 1-1/2 by 3-1/2, and a 2x6 was 40% stronger. There is one problem here - there is more surface area for energy transfer. 2x4 exterior construction is not allowed without insulation upgrades to make the walls have an R-21 value. Some exterior stud walls have spacing on 24” for energy efficiency. More insulation, less studs to transfer heat from inside the building to outside. Washington State is about to raise the energy code 30% to reduce energy consumption and I am not sure how this is going to be accomplished. Stud spacing makes a significant difference in looking through an infrared camera. You can see every stud in a wall because of this. If we, as a country, want to relieve ourselves of foreign oil, there must be changes in the way we drive and build.

I'm not bashing you. I think it's amusing to see the inconsistency of the code and its interpretation. I do find it sad that you could ask 10 code officials the same exact technical question and get 15 different answers (that's counted right, because some waiver on what's correct in their opinion). Kind of like tax codes - they're black and white with lots of gray.

Also, with the energy loss according to infrared, would this truly be considered energy loss or energy stored, since wood is supposedly known for storing energy and transferring it out later according to most log home producers? I do find a log home to have a better radiant heat/cooling feel about it.

A lot of old buildings are torn down not because of the rough cut lumber (which catches the fault), but because of poor construction techniques and workmanship. I'm glad to see techniques improve, but it doesn't mean all the older ones were all wrong.

Contributor M represented section 502.1 in his earlier post. I did not find the same information listed in other places, but it is there. This section does not make any exceptions, even though there are at least 200 exceptions in other areas. I could not find one for section 502.1. The only other building material in the code is engineering wood products and metal stud for this purpose.

From my reading I would say that SIP, timber frame, straw bail, log home and I am sure I could come up with a couple others are not allowed.

On another note I think it was MI that showed a map of the counties that use the IRC code. It was only about 10% of them.

This actually happened when I was doing my internship. There was a bad 6x8 header and I brought it to the attention of the inspector that I was inspecting with. He chose to do nothing about it. This made me worry about what he was thinking. When I asked him, he said it was in a place where there was very little loading on it. So he let it go. I was learning and had little background in what I was supposed to be inspecting.

The answer is no, as long as there is a grade stamp on the piece of wood.

When I come out to inspect a structure now, the first thing I look at is the plans, and I take them with me when I am inspecting the building. The structures much match the plans. Any deviation from the plans requires that they be resubmitted for approval. Load points on a structure are very important and must be carried all the way to the soil. The foundation is the most important part of a building. Being below the frost line, expansive type soils, load capacity of the soil, the footing dug into the same soil layer are all very important. One of the most interesting things I learned in college was if the footing was not in the same soil level, you could experience a serious problem with a term called “differential settlement.” This is when after the building is done; it slowly sinks, and compresses the soil under the footing. Most of the time it is about ¼ inch in the first year and about another ¼ inch in the structure itself. Building construction wood must be below 19% before it is covered per code. In the first year, after a building is done, the wood slowly drops in moisture content to about 10%. This is the reason why after the first year there are cracks in sheetrock where there are wall to ceiling, wall to wall joints. If the footing was not built in the same soil level, the footing in one corner could compress ¾ of an inch and in another corner only ¼ of an inch. Do you see what the problem is here? There could be cracks in the foundation and it the walls from this.

The inspection course, which is a year full time at college to get your certificate, really makes you think about issues I would have never thought about. I started in the construction trades at a very young age and have built high rise buildings, houses, bridges over waterways, docks, everything except dams. School got me to learn about so many other issues that I never cared about before. There really are two sides in construction - the general contractor or builder, and the governing agency for inspection. I teach construction classes at the college now, and the students for the first time ever get to hear from me what an inspector is looking for. This has never happened in the past, where the only instructors have been contractors.

Timber framing falls under the IBC because of the type of construction it is. Most houses are classed as a V-B (five-be) construction with little fire protection and loaded with combustible materials in walls, ceilings, floors and roofs. Log houses and timber framing fall under a different classification and are not in the IRC and are a IV-B (four-be). So much of this falls under what the structure is going to be used for.

Please give me a code section cite for this? I believe you are mistaken. Design values are adjusted for wet service, defined as use in a location where the wood will be above 19%.

The IRC has 2 methods that may be used. The prescriptive path, building according to the prescriptions written in the IRC using its' tables and prescribed methods of construction. The second path is engineered. When residential construction steps outside of the IRC's prescriptions, the construction must be built in accordance with accepted engineering practice.

"R301.1.2 Engineered design

When a building of otherwise conventional light frame construction contains structural elements not conforming to this code, these elements shall be designed in accordance with accepted engineering practice. The extent of such design need only demonstrate compliance of nonconventional elements with other applicable provisions and shall be compatible with the performance of the conventional framed system"

Log homes, timber frame homes and engineered products used in residential construction are still under the IRC and use this method. A heavy timber does not kick one into commercial code. For wood products the IRC defers to the NF&PA's National Design Specification for Wood Construction. I have 2 sets of plans on my desk now for bid. One is a log home, the other is conventionally framed with a timber framed great room, both go through the provisions of the IRC. I have built complete timber frame homes under the IRC. The "conventional" parts of the homes use the prescriptive code, those parts that step outside of the prescriptions in the IRC are engineered. No IBC.

Contributor V, the methods and materials you mentioned are not prescriptive but they are most certainly allowed under the IRC.

Log homes now have a prescriptive standard developed by industry and the ICC, the standard is published by the ICC and is titled ICC 400-2007 Standard on the Design and Construction of Log Structures. The TF community is working to develop a similar prescriptive standard. I've attended a conference where the NF&PA's Buddy Showalter discussed the progress of the TF standard to date. These are being written so that common elements of both these types of buildings do not have to be engineered each time but will be prescriptive, thus streamlining design and construction.

For grading under the alternative materials section...

"R104.11

Alternative materials, design and methods of construction and equipment.

The provisions of this code are not intended to prevent the installation of any material or to prohibit any design or method of construction not specifically prescribed by this code, provided that any such alternative has been approved. An alternative material, design or method of construction shall be approved where the building official finds that the proposed design is satisfactory and complies with the intent of the provisions of this code, and that the material, method or work offered is, for the purpose intended, at least the equivalent of that prescribed in this code. Compliance with the specific performance based provisions of the ICC codes in lieu of specific requirement of this code shall also be permitted as an alternate."

Going back to an inspector asking for a full dimension 2x because it is 40-60% stronger than nominal. Design determines the strength required. Grading establishes allowable stresses. These drive required dimension. There is no provision in this equation for an inspector to require another dimension because it makes him feel good. If a span table or engineering call for a 2x10, the inspector cannot require a 2x12, as this would be enforcing personal opinion. An 8x24 is over 225 times stronger than a 2x4, so where does it end? This would be exceeding one's authority. May I exceed code minimums if I choose to or if I agree with your suggestion? Most certainly, I do so frequently.

“R802.1.3.5 Moisture content. Fire-retardant-treated wood shall be dried to a moisture content of 19 percent or less for lumber and 15 percent or less for wood structural panels before use. For wood kiln dried after treatment (KDAT) the kiln temperatures shall not exceed those used in kiln drying the lumber and plywood submitted for the tests described in Section R802.1.3.2.1 for plywood and R802.1.3.2.2 for lumber.”

And in the IBC

“2303.1.8.2 Moisture content. Where preservative-treated wood is used in enclosed locations where drying in service cannot readily occur, such wood shall be at a moisture content of 19 percent or less before being covered with insulation, interior wall finish, floor covering or other materials. 2303.2.5 Moisture content. Fire-retardant-treated wood shall be dried to a moisture content of 19 percent or less for lumber and 15 percent or less for wood structural panels before use. For wood kiln dried after treatment (KDAT), the kiln temperatures shall not exceed those used in kiln drying the lumber and plywood submitted for the tests described in Section 2303.2.2.1 for plywood and 2303.2.2.2 for lumber.”

Also in table 2304.7(1) subnote “C”

Not to disagree with you, but timber framed and log houses do fall under type IV construction.

“602.4 Type IV. Type IV construction (Heavy Timber, HT) is that type of construction in which the exterior walls are of combustible materials and the interior building elements are of solid or laminated wood without concealed spaces. The details of Type IV construction shall comply with the provisions of this section. Fire-retardant-treated wood framing complying with Section 2303.2 shall be permitted within exterior wall assemblies with a 2-hour rating or less. 602.4.1 Columns. Wood columns shall be sawn or glued laminated and shall not be less than 8 inches (203 mm), nominal, in any dimension where supporting floor loads and not less than 6 inches (152 mm) nominal in width and not less than 8 inches (203 mm) nominal in depth where supporting roof and ceiling loads only. Columns shall be continuous or superimposed and connected in an approved manner.

602.4.2 Floor framing. Wood beams and girders shall be of sawn or glued-laminated timber and shall be not less than 6 inches (152 mm) nominal in width and not less than 10

inches (254 mm) nominal in depth. Framed sawn or glued-laminated timber arches, which spring from the floor line and support floor loads, shall be not less than 8 inches

(203 mm) nominal in any dimension. Framed timber trusses supporting floor loads shall have members of not less than 8 inches (203 mm) nominal in any dimension.

602.4.3 Roof framing. Wood-frame or glued-laminated arches for roof construction, which spring from the floor line or from grade and do not support floor loads, shall have

members not less than 6 inches (152 mm) nominal in width and have less than 8 inches (203 mm) nominal in depth for the lower half of the height and not less than 6 inches (152 mm) nominal in depth for the upper half. Framed or glued laminated arches for roof construction that spring from the top of walls or wall abutments, framed timber trusses and other roof framing, which do not support floor loads, shall have members not less than 4 inches (102 mm) nominal in width and not less than 6 inches (152 mm) nominal in depth. Spaced members shall be permitted to be composed of two or more pieces not less than 3 inches (76 mm) nominal in thickness where blocked solidly throughout their intervening spaces or where spaces are tightly closed by a continuous wood cover plate of not less than 2 inches (51 mm) nominal in thickness secured to the underside of the members. Splice plates shall be not less than 3 inches (76 mm) nominal in thickness. Where protected by approved automatic sprinklers under the roof deck, framing members shall be not less than 3 inches (76 mm) nominal in width. 602.4.4 Floors. Floors shall be without concealed spaces. Wood floors shall be of sawn or glued-laminated planks, splined or tongue-and-groove, of not less than 3 inches (76 mm) nominal in thickness covered with 1-inch (25 mm) nominal dimension tongue-and-groove flooring, laid crosswise or diagonally, or 0.5-inch (12.7 mm) particleboard or planks not less than 4 inches (102 mm) nominal in width set on edge close together and well spiked and covered with 1-inch (25mm)nominal dimension flooring or 15/32-inch (12 mm) wood structural panel or 0.5-inch (12.7 mm) particleboard. The lumber shall be laid so that no continuous line of joints will occur except at points of support. Floors shall not extend closer than 0.5 inch (12.7 mm) to walls. Such 0.5-inch (12.7 mm) space shall be covered by a molding fastened to the wall and so arranged that it will not obstruct the swelling or shrinkage movements of the floor. Corbeling of masonry walls under the floor shall be permitted to be used in place of molding.

602.4.5 Roofs. Roofs shall be without concealed spaces and wood roof decks shall be sawn or glued laminated, splined or tongue-and-groove plank, not less than 2 inches (51 mm) thick, 11/8-inch-thick (32 mm) wood structural panel (exterior glue), or of planks not less than 3 inches (76 mm) nominal in width, set on edge close together and laid as required for floors. Other types of decking shall be permitted to be used if providing equivalent fire resistance and structural properties.

602.4.6 Partitions. Partitions shall be of solid wood construction formed by not less than two layers of 1-inch (25 mm) matched boards or laminated construction 4 inches (102 mm) thick, or of 1-hour fire-resistance-rated construction.

602.4.7 Exterior structural members. Where a horizontal separation of 20 feet (6096 mm) or more is provided, wood columns and arches conforming to heavy timber sizes shall

be permitted to be used externally.”

We do tell builders that they should not cover walls and ceiling unless the wood is dry to the touch. This is what I was told to do. The jurisdiction I have worked for uses the 19% rule because my bosses interpret this to be so. I have a moisture meter although I am not allowed to use it.

I had forgotten that I have all the 2003 codes in my computer. Most residential types of construction use both IBC and IRC. I see it all the time on plans. Example: 2x2x1/4 plate washers are used in the IBC, but if you use the IRC they must be 3x3x1/4”. I do find this very confusing. You are allowed to mix and match both code books. Most of the time if you use type IV construction (Timber framed and Log houses), all this information comes out of the IBC. As I understand it, IRC is prescriptive construction and engineered comes out of IBC. Since Timber framing and Log houses are not in the IRC they have to come from the IBC.

This is how I see it, although before I did anything to someone, I would discuss this with my peers. I have stuck my foot in my mouth more than once and had to suck it up.

R602.3 Design and construction, this is in the wall chapter but you will find it reworded in other chapters for each assembly;

"Exterior walls of wood frame construction shall be designed and constructed in accordance with the provisions of this chapter OR in accordance with the AF&PA's NDS."

This has just described the prescriptive or the engineered paths in the IRC. Pull down your copy of the NDS... Notice its methods go right up through heavy timber, round sections, everything we're discussing here and more. If I use an I beam in a house I'm not kicked into the IBC. If it is for a 1 or 2 family structure the use dictates the IRC, not the design method or materials used. Yes, you can build a heavy timber commercial building and the code is more restrictive on that type of construction. Log and timber 1 and 2 family homes are constructed under the IRC.

I don't know of a better way to explain it... but I'm gonna stomp you at the appeal hearing.

The moisture content provisions you cite from the IRC do not apply to solid sawn products. If you remember the charring issues with FRT some years ago, that prompted that section. Your jurisdiction is apparently enforcing opinion in this regard and not law. You can recommend and advise on best practice, and I do agree, however you cannot enforce your opinion legally. I've metered logs and timbers over 35% many times, don't like it, have used it in court against suppliers who advertised otherwise, but that is none of your affair. Whenever an inspector tells me something isn't code I ask him to cite the section and describe how I failed to comply. This forces him to read the codebook and then we can discuss interpretation. I generally don't get opinion disguising as code a second time; they come prepared. It also means I need to be prepared, as it should be.

Yup, I do know what shoe leather tastes like. I also try to sail so far above code it never becomes an issue, but that is an option I choose and not a requirement.

If you see improperly graded structural framing in a building it is in your authority to ask that it be removed. I will point to the grade stamp and refuse; that is my proper recourse. You will then copy the grading agency name from the stamp and the mill number and call the agency, asking them to come out and re-grade. If the agency grader agrees with you after the re-grade, the material will be replaced and then I must remove and replace the material per your request. In the case of the WI native lumber grading act, you would contact DNR and they would be required to send someone out. The system still works.

Regarding MC limits, they are given so that one knows the size at the time of grading and the MC at that time. There is a 1% size change for 4% MC change allowed (in general), so that when lumber is measured at a different MC, the size change can be accommodated or understood. The MC of framing lumber when installed is not specified, but in use, it will generally come to around 12% MC or a bit lower.

A stud has #3 grade knot and slope of grain restrictions and close to #2 wane restrictions, to give an adequate nailing edge. This is not a stick to interchange into a horizontal application, it's a stud.

"HT- Heat treated to the international standards for core temperature and length of time sufficient to kill a series of pests. (This is often combined kiln drying of lumber, to produce a stamp reading KD-HT)"