Question

I make custom bows, using strips of wood that are laminated together. Buying these strips is quite a bit more expensive than buying the wood and cutting them myself would be. The problem with this is that some of the strips need to be tapered. I have thought about making a jig and cutting them on a table saw, but I’m not sure if there is a better way or not. The dimensions on the strips are .110" thick 2" wide 36" long with a .002 per running inch taper. Am I on the right track or way off?

Forum Responses

(Solid Wood Machining Forum)

From contributor S:

Yes, you can probably figure out a relatively safe way to cut these parts on a saw, but as a craftsman of custom bows, have you got a good bench plane? Seems like with a well-tuned plane, you could produce these tapered parts with just a few passes.

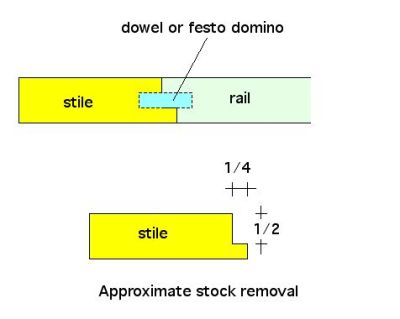

Take two pieces of 3/4 ply (cabinet, not construction ply), each 3 3/4 by 36. Mark a line 7/8 in from each side edge on each piece. Rip five strips 1/8 thick, 13/32 x 38 1/4. Cross cut off four 1” pieces from the least good strip. On each ply blank, glue and clamp two strips down 2 1/16 apart and outside the marked lines. Do not nail, staple, or screw them down - glue only (any evidence of fasteners and no one will machine it). After 30 minutes, scrape any glue out from the inside and outside corners of the track that you’ve formed.

Slip a short piece of 2” stock into one end of the track, glue in two of the 1” pieces parallel to the main strips and evenly spaced as stop blocks. Don’t glue them beside the long strips - leave space for chips to escape. You now have two rough pieces with a 2 1/16 channel in them to capture your rough, 2” stock.

Find a shop in your area that has a jointer and a surfacer. Surface one piece so that the strips are a bit over the thickness that you want your final stock to be - say about .114 - .115. (I'm assuming that you have a dial caliper.) On the other piece, mark a line 30 inches up from the stop blocks and carry that over to and across the edges. Set the jointer for a very fine cut. Drop the piece down on the 30" mark and joint the strips. This will taper the rails by the jointer’s depth of cut. Keep doing so until the inside edge of the stop blocks measures .050 (.110 - (30 x .002)). You now have two pieces with clean rails; one is flat, the other tapered.

Rip four strips 3/8 square x 36. Glue one along the outside edge of each rail to provide a lip to capture a 4 1/2 hand plane, which has a 2 3/8 wide blade. Cut two cleats about 1x1, each 6” long. Screw one down across the bottom of the open end of each jig. You can put this cleat in a vise (or just set it over the edge of a bench) to keep the jig in place while you plane.

Buy a 4 1/2 smoothing plane; Lee Valley has a nice one for $200. You can get a good classic Stanley for half that from a dealer, but you might need to true and adjust it (skills you might not have right now). Buy a sharpening jig and learn to sharpen the blade; this will be one of the very few times when you want to sharpen the blade *square* with no arc.

Saw your laminating stock 1/8 x 2 x 30. Adjust the plane to take a *light* cut the full width of the blade. My guess is that you’d want fairly clean stock with very little grain run out - it should plane easily. Drop a rough stock into the parallel jig and plane the surface clean. Drop the clean stock into the tapered jig, clean surface down, and plane the other face clean and tapered. Glue up the day that you plane them.

If you're using hard maple, ripping 2" stock might be beyond what a contractor's saw will do comfortably. If you purchased a good plank, you might be able to have a local shop rip it into 2x36" billets, resaw them to 3/16, and surface them to 1/8 for less than purchasing 1/8 stock. You could store that stock until you needed to use it and plane the day you work it. But recognize that stock that thin will take on water very quickly when it's humid. You'll want to buy dry stock and store in sealed plastic containers until use.

As I recall, bow (hunting, long, cross, etc.) strips are riven first (green) for the straight grain, then worked to thickness/shape for grain continuity. Hand or machine planing will not give much control over cutting through long fibers.

One type of machine comes to mind that could do it for you, and that's CNC, but that's big dollars. May be worth it to you, though.

Comment from contributor T:

I would suggest trying to use one of your purchased laminations as a sled. Place a block of wood on this lamination and run it through a drum sander. This will duplicate the taper. From then on, use your new block to taper your laminations. 60-80 grit works well with SmoothOn heat cured epoxy.

I recommend your table be no more than 18 inches wide and no more than 12 inches deep so it gives you room to maneuver. Next, make a 1 1/2 inch tall (if you use two inch laminations, then it should be 2 inches tall) jig to be clamped to the table. The side facing the spindle and the side contacting the table must be perfectly square. Take one of your laminations that mic's out to your tolerance in taper and consistency from side to side and place it against your jig. Clamp one side fairly tight, leaving enough space between the jig and the spindle for your parallel lamination to pass and yet grind away the material necessary to give it a taper. (IMPORTANT SAFETY TIP: You must ALWAYS push your parallel against the direction of the spindle/belt! Hold your laminations firmly and keep your hands AWAY from the sand paper! 36 grit sandpaper will surely take skin away as wells as wood!)

Determine the tip thickness you want for your particular lamination to be "ground" and using a scrap piece of material, place it next to the butt of your pattern lamination and place them side by side and between the jig and the spindle. Adjust your jig until you've got the desired gap by using scrap material to check your thickness. Slowly push in the material and then retract carefully and check with a micrometer. You'll get the hang of it. When you've got your desired setting for your jig and it's clamped firmly at both sides of the table, you are now ready to place the parallel lamination facing the sanding surface, together with the pattern lamination which will go against your jig, on the table and gripped firmly together and start them through the gap in the jig/sanding surface. Ensure you maintain a slow, steady feed which will ensure grinding consistency.

I start my lamination "sandwich" feeding with my left hand holding the two laminations firmly, and when about 12-15 inches has passed through the grinding location, I transfer feeding and hold/feed with my right hand by reaching across, ensuring I keep my hands and body parts AWAY from the sander, and keeping the SAME speed/feed rate at all times. If you stop, you'll have an obvious divot in your lamination. It may take a few times for you to get used to it, but with just a few passes with scrap material, you'll be ready to do it for real. It surely works.

The next method I recommend is to use a drum sander. I make a pattern using a board at least one inch thick on which I place laminations. I glue a "stop" on the pattern on the opposite end that you begin feeding, to keep the lamination from slipping. You make this pattern in the same was as described above. This method controls the feeding for you and you can do several laminations at one time due to the width of the sanding belt on the drum sander. However, I recommend laminations be ground using AT LEAST 50 grit paper, and I definitely prefer 36 grit. 36 grit can be difficult to obtain for drum sanders. The reason I prefer 36 grit is it gives you a great glue surface and once wiped down with acetone, doesn't leave you with residue problems that would affect glue-up.

Speaking of glue, I've used Epon Versamid from Bingham Projects since 1985 and have never had a de-lamination occur. In addition to using Epon Versamid (and I've tried most all of them for comparison) I use my own laminations utilizing the above methods of grinding. I have a rule that I don't glue up with "old" laminations because wood oxidizes and I believe a freshly ground glue surface works best. Combined with this philosophy, I also wipe off all glue surfaces with acetone and pre-heat them with a hot-air gun (hair dryer works too) just prior to glue-up.

Finally, I ensure that everything fits the bow form and is clamped securely (I use my own clamping system based on U-Bolts for the handle section and "C" Clamps for the limb section). I think this will help anyone to be successful in bow building and hope these tips are found helpful. Remember there are many methods. I don't claim mine are best, they just work for me. Stay safe and enjoy the wonderful art of the bowyer!