Straightening Cupped Slabs of Pine

Detailed information and advice on removing cup from wide boards. April 30, 2009

Question

A client has provided a set of four large 5/4, 96" X 28" x slabs (flat sawn, live edge, full width of tree) of pine for use in a special project in which they'll be used whole. The wood is fully dry. Only one board is significantly cupped. I have a pretty good understanding of moisture and wood and the cause of cupping, but in researching the straightening of cupped wood, I've found surprisingly conflicting info.

While most, (including some trusted WOODWEB advisors), advise introducing moisture to the concave side, and/or heat to the convex side, Mr. Flexnor (and others), suggest nearly the opposite. They suggest laying wet towels on the convex side, clamping tangentially (width-wise), and adding weights in the center to further coax flat as it dries.

I've gone with Flexnors method, and while it's only been two days, they haven't gotten much straighter. I'd love to hear opinions of those with success in this dept. Timing tips and details greatly appreciated:

-How long should I let dry before repeating the treatment?

-How long before unclamping/weighting? -

-If using a steam iron/wet towel, which side? (Since that is both heat and moisture.)

Forum Responses

(Furniture Making Forum)

From contributor C:

Take a slab of 1/4" thick board to speed the experiment and wet one side. I think you will find that the wet side will become convex, and the concave side is the dry side. Draw your own conclusions from that.

From contributor M:

Set the slab outside on the grass in the morning, convex side up. As the morning dew burns off, your slab will become flat and then it'll cup the other way - check often.

From contributor W:

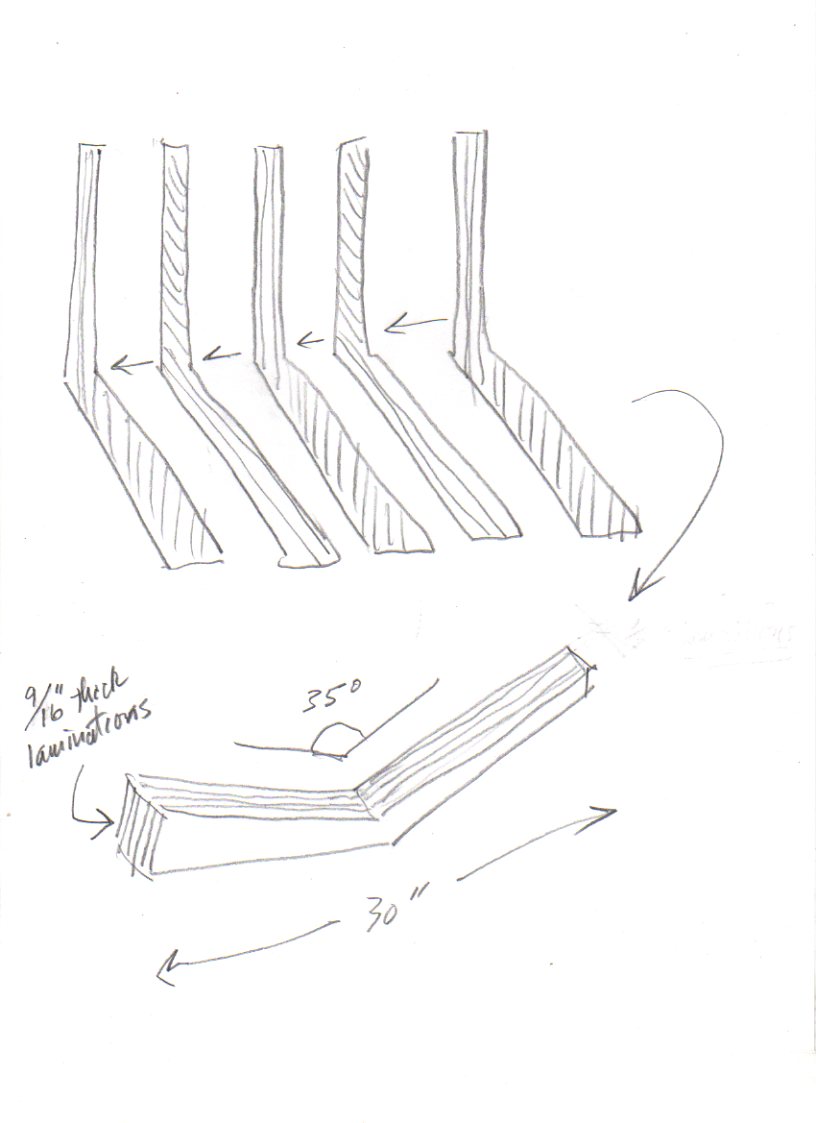

Rip the slabs down to boards 3-4 inches wide, run one face across the jointer just enough to give you a flat face to work with, joint both edges then glue the panel back together in the original order and orientation they were in then plane down the panel. The glue joints will be pretty much imperceivable.

You could rip saw kerfs in the bottom of the panel 2/3 of the panel thickness deep spaced 2-3 inches apart then attach battens across the panel and fill the kerfs with glue. After the glue dries you should be able to take off the battens and the panel should stay flat.

From Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

If you can flatten a cupped piece, you are lucky indeed, as it is almost impossible to do. The water techniques are not terribly effective. Flexner is correct. The best flattening can be achieved by quickly rewetting the convex side. It will try and expand, but it cannot do so. As a result, it will develop what is called compression set. (In brief, some of the cells that are trying to expand will squish.) Do not let water go beyond the surface (maybe 1/4 inch). In other words, do not wet for more than a few hours. Remove the water and then let this convex side dry (not too fast, such as using a hair drier) and shrink. Hot water works better. The problem with this technique is that it is hit and miss as far as how much water to add. Oftentimes, two treatments are no better than one. Further, it is not permanent; the piece will cup if rewetted.

An alternative method is to steam the piece getting it soaking wet throughout and hot. Then bend it flat and then dry it will holding it flat. This again is not totally permanent and is hard to do.

From the original questioner:

Thanks Gene and everyone. The rip and glue wasn't an option here and I hadn't read Gene's post yet (which does makes sense), so I went with the old-timey method but with a twist. Without clamps or weight, I laid the boards concave-down on cardboard damped with boiling water), convex-up, in direct sun, with the addition of blasting the bottom (concave) with a household steamer. To my surprise, a mere three hours later and the cupping completely over-corrected! I then flipped and repeated the technique for 1.5 hours. I then stickered and weighted the boards with several hundred pounds for two days. It worked - for my purposes though by no means perfect. They've held shape so far, we’ll see. Also keep in mind my trials here were soft pine slabs only 4/4 and 30" widths. It’s likely very different results with different woods.

From the original questioner:

Also just for us newbies, I wanted to add to Gene's informative post above (apparently the technically proper method) that this method calls for several bar clamps across the width of the board before wetting. Thus when he says 'the cells want to expand but cannot, it is because the width of the board is restricted by clamps.

From Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

The width is also restricted by the dry core which is not expanding (because you are wetting fast so only the surface wets).

From contributor H:

If the wood is "fully dry" then why not joint one face and plane for thickness? It seems to me adding water will only affect the outcome for a short amount of time. I'd put then on the CNC, center the pods and with a fly cutter face one side.

From Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

The reason that this wetting works is that the swelling is restrained, so the piece develops set. This means that the one face will shrink differently or be at a different size than the other and this will mean a flat piece in the end.

From contributor R:

I am with contributor M on this one. Put it in the sun, cup side down and check often. I have used this method many times and it always works for me.

From contributor H:

Ok, so I am at a loss. If the board was dried and set and you added water to one side I could see how that would push the board flat. When the wet side then dried why wouldn't it return to its original un-flat state?

From Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

If wood was a perfectly elastic material, then what contributor H would be true. However, wood is also plastic, meaning that under stress it will flow and form a new size. So, by adding water to one side, as I stated, we will get that side to try and swell, but the restraint offered by the rest of the wood will not let it swell, so the wood then develops set (meaning that its size will be smaller than "normal"), which is how we get it to be flat after re-drying.