Analyzing Wood Species, Grain, and Sawing Methods

Here's a long and complex (but very informative) thread that starts off with a wood identification problem, moves into a discussion of wood pore structure, and then takes off on an interesting tangent about quartersawing, flatsawing, and other methods for piecing out a log. March 22, 2013

Question

Any ideas regarding what type of wood this is below? The characteristic that my client is after is the straight grain and open pores to accept what looks to me like a white glaze. The redness in the photo is just glare. The color is actually more of a grey, which is what I'm after. I have been able to get good color and grain using QS white oak, but the grain is too tight to accept any glaze. Padduck has good grain characteristics, but I can't get the gray color short of painting it. The picture is from a piece of furniture seen in a store, so who knows what was used in what country.

Click here for higher quality, full size image

Forum Responses

(Cabinetmaking Forum)

From contributor W:

Wenge?

From contributor D:

It could be quarter cut ash.

From contributor K:

That looks just like rift white oak.

From contributor J

Have you felt the weight? Sassafras looks a lot like oak in grain but is considerably lighter in weight. It is more brownish grey then white oak.

From the original questioner:

Contributor J - no I was not able to feel the weight. I receive the picture from a designer I work with.

From contributor B:

Since quartered white oak was close, rift red oak should be perfect. White oak has closed grain so will not accept glaze but red oak has open grain pores. Bleached oak turns grey.

From contributor G:

To contributor B: "White oak has closed grain". Please explain this to me or maybe Dr. Wengert will add to the discussion as well.

From contributor B:

If you want to know how sap flows and wood grows, we probably should consult Dr. Wengert. Try this: Cross-cut a thin slice of both white and red oak and then hold them up to the light and you'll understand. What you'll see is light shining straight through innumerable little (open) holes of red oak while white oak blocks the light. The open pores of red oak act as an absorbent sponge which needs to be sealed or filled for adequate protection. The white paste filler in this case may be part of an "antique" finish.

From contributor G:

The stain appears to be accepted the same way as red oak?

From contributor B:

Red and white oak will both stain anywhere from blond to black and are nearly indistinguishable when finished.

From contributor G:

When I think of closed grain I think of maple which is hard to stain with a pigmented stain. I'm going to school on you in that it appears there is more than one definition of closed grain?

From contributor B:

Closed Grain: Closed or non-visible cellular pores, as pertaining to vessel elements of hardwood only.

Open Grain: Visibly open cellular pores.

Close Grain: As in distance between annual growth rings, synonymous with "Fine Grain", as pertaining to texture (sometimes erroneously referred to as "Closed Grain").

Wide Grain: Greater distance between growth rings, synonymous with "Course Grain".

The above terms are (loose) layman adjectives used to describe perceived wood variables with no specific scientific quantification. I believe this is correct but we may need Dr. Wengert after all.

From contributor G:

Would white oak then have closed vessel elements and also visibly open pores? It would be good if they gave examples of close grain and wide grain. I'm not quite getting this, I guess I will have to read up on it.

From contributor B:

White oak has closed pores, which renders it "non-porous". This makes it very suitable for boat building and outdoor application but unsuitable for wood fillers (since there's nothing to fill).

From contributor G:

Then what are those holes I see in white oak? Am I imagining this? Why does white oak stain infinitely easier than maple? This simply does add up.

From contributor B:

Blotchy wood stains are caused by poor or inconsistent penetration of the stain into the wood. Maple has very fine, hard grain that's difficult to sand and prepare to a uniform surface. Maple is also very uniform in color to begin with so that any non-uniform absorption of the stain is accentuated. The glazed, open pores of the wood in question is "without question". White oak doesn't have them, red oak does.

From the original questioner:

I'm real close - see photo. This is QS red oak. The only issue now may be the rays perpendicular to the grain. Is it correct that rift sawn red oak would not have these? My supplier only has QS. In a QS log, is the center board of each quarter, which is perfectly radial to the center, the same as a rift sawn board? If so, I should be able to pick through the stack for boards without rays?

I could order rift sawn from Walzcraft, but I'd like to have continuous grain from one drawer front to the next from a single board. Not sure if Walzcraft would do this (or if I could afford it).

Click here for higher quality, full size image

From contributor B:

The main reason for buying quartersawn oak is for the highlighted ray fleck (that's what you're buying). The main reason for ordering rift is the straight grain without the fleck. Rift cut boards are cut with growth rings strictly perpendicular to the face. It's the only lumber cut from radial lines (the log is actually rotated with each cut). The wood between these radial cut-lines is wasted.

Flat and quartersawn boards are both cut sequentially. According to timber cut diagrams, only one board from a quartersawn stack may be a true rift cut. The lumber yard will tell you that there's little difference but that's because they're not stocking true rift. There is a difference. If you go with quartered oak, you will see ray fleck (if not, look closer). If you're seeing ray fleck in lumber that's supposed to be rift, it may have been culled from the quartersawn stack to sell for a premium as rift.

From contributor B:

Drawer fronts? Why not veneer? Why not order veneer samples and play with them first?

From Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

One problem we see here is that the word "grain" has seven or more different meanings. One of the later postings also gives a definition of rift - another word with poor definition, but the ray fleck is certainly less obvious. I have never heard that rift oak lacks any ray fleck. For more discussion, see past WOODWEB postings.

Another term with a poor definition is "kiln dried" as the MC, especially in hardwoods, is not defined specifically. With respect to the large white and red oak pores or vessels, in most (but not all) of the 20 commercial species in the white oak group, the vessels in the heart wood are plugged (technical term: occluded). In red oak, the vessels are fairly wide open. Note that the vessels run up and down in the tree or lengthwise in lumber. Note that sap flows upward in the sapwood which is open grain (using one definition of grain). Regarding the picture, the absence of any ray fleck would seem to drop it out of the oaks. I suspect it is hackberry, quarter, or rift.

From the original questioner:

Thanks again Contributor B and Gene. I just read back through the Knowledge Base on QS vs rift. So what I want to minimize the rays is 45-75 degree growth rings, which is technically rift sawn, but by most suppliers definition QS? The growth rings in my "QS" sample are very close to 90. It seems crazy that these definitions are completely reversed.

Gene, nice call on the QS hackberry, but I'm not sure I could find it so I'll probably have to make do with oak.

Contributor B - I am going to try veneer and see if I can get the same result as the sample. Now do I need QS or rift? My head is starting to hurt thinking about this. Maybe a nice painted MDF?

From Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

Note that many producers sell quarter and rift together, just to avoid any confusion, maybe.

From contributor B:

The various descriptions or diagrams can be confusing and perhaps in error but it's actually not necessary to sort through them. All that's really required is that you get what you need. A trip to your local hardwood store for a close inspection of various veneers may be your best bet. What you'll discover is that the "ray fleck" (flake) you're trying to avoid is minimized or eliminated in rift cut oak.

Back to science - the "fleck" is the medullary rays which are like vertical ribbons or sheets (fin-like spokes) radiating out from the center of the tree and cutting the growth rings at 90 degrees. When they pass obliquely through a plain sliced or quartered board, their thin structures are elongated or accentuated and appear as "flake" on the surface. Since rift boards are cut parallel with these medullary rays, their cell structures are greatly minimized or not apparent. Again, "seeing is believing" and in the case of wood, "what you see is what you get". After that, you can dispense with science.

From Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

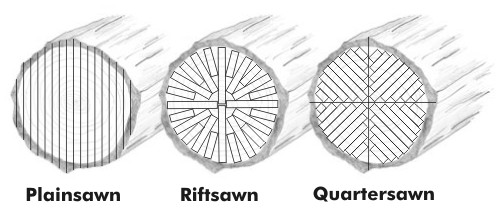

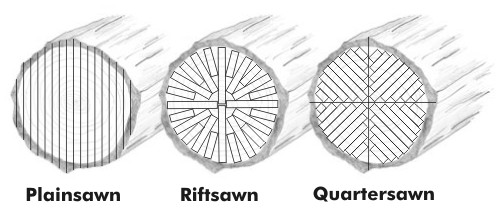

Quartersawn has the face exactly parallel or within 15 degrees of parallel to the rays. The rays run radially outward from the center. Hence q-sawn has the most striking fleck. Rift sawn is 45 to 75 degrees, but as the rays do have thickness, even when not perfectly parallel, the fleck will be seen, although not as obvious as the angle increases. Flat sawn is 45 to 90 degrees.

Can you find rift sawn in the NHLA grading rules or listed separately in the major pricing documents? The NHLA says that if the fleck is obvious, it is quartersawn.

From contributor B:

Gene, according to diagrams I'm looking at, only rift has the face exactly parallel to radial rays. The other boards are all cut sequentially to each other in one way or another. In addition, there appears to be two different ways to cut "quartersawn" boards, one of which is definitely not radially. Either way, "will-call" at the lumber yard is better than a thousand words or diagrams.

Click here for higher quality, full size image

Click here for higher quality, full size image

From the original questioner:

To contributor B: I agree, I'm going to try rift and quartered and see what looks best for my project. That aside, your last post is exactly what has me confused. Your diagrams are the same ones I found and are completely opposite of Gene's definitions.

From contributor G:

My quote: "Would white oak then have closed vessel elements and also visibly open pores?" Dr. Wengert's quote: "With respect to the large white and red oak pores or vessels, in most (but not all) of the 20 commercial species in the white oak group, the vessels in the heart wood are plugged (technical term: occluded)." So is my understanding correct Gene?

From Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

The log end diagrams are incorrect. The middle one will produce 100% Quartersawn and the right one, both quarter and rift. The left log picture is totally incorrect, as the four pieces from the middle of the log are actually quartersawn. This picture should be labeled as “live sawing”. There would be a different pattern for flat sawing (also called plain sawing). Likewise, the top half of the single logic true, under the three logs, is incorrect as the pieces close to the center will be rift and quarter.

In the lumber pictures, note that you can see the fleck faintly running at a bit of an angle to the upper left. Note the high waste when quarter sawing only. This is mainly why quarter lumber is so expensive. In most cases, the mills will saw according to the right picture, making quarter and rift, which are often sold together. Note the decreased waste when this technique is used. The blue piece of lumber labeled "rift and quartered" is actually 100% quarter. Rings are at 90 degrees to the face. (Note that I used to manage a sawmill for eight years, which is how I am so familiar with this.)

From Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

To contributor G: I am it sure what you mean by pores, as vessels and pores mean the same to me. Most white oak pores in the heartwood are plugged and that is why white oak is used for liquid barrels - wine, whiskey, etc.

From contributor G:

Dr. Wengert - when using pigmented stain white oak sure seems to have vessels or pores and accept the stain well, which is not the case with small pores as with maple. If the vessels become occluded some distance from the surface I could see where it would accept stain well and also would not pass water through the vessels. Is the case?

From contributor B:

To contributor G: "Would white oak then have closed vessel elements and also visibly open pores?" Answer: No - no open pores, no visibly open pores. White oak is occluded. The Questioner has already discovered that the grain is too tight to accept any glaze.

To the original questioner: In fairness, Gene’s definitions are exactly as I have read them from other sources. I believe that rift and quartersawn have been used interchangeably for quite some time and definitions have been blurred or misunderstood. Notice on the lower blue and yellow diagram that the yellow boards are designated "rift and quartered" (arrows pointing up and down). This illustrates how rift boards are culled from this type of quartered lumber.

From Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

For at least 50 years, the NHLA has defined quartersawn lumber as lumber showing the ray fleck. Check the rules for the exact definition and requirements. Their definition is used exclusively in the trade when selling or buying. It has not changed.

From Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

As a sawmill manager, I hope that I know what quarter, rift and flatsawn lumber is? In the industry in the US, plain sawn is not widely used. In addition to this appearance factor, other differences between flatsawn and quartersawn include: Flatsawn shrinks and swells in thickness about half as much as quartersawn. Quartersawn shrinks and swells in width about half as much as flatsawn. (This can be important for exterior siding that is subject to frequent wetting and drying. It can also be important for floors and other products that cannot tolerate much movement.)

Knots will be round or slightly oval with flatsawn, but will be long spike knots in quartersawn. (Generally, spike knots lower the strength more than round knots.) Shake and pitch pockets in the log will affect fewer pieces when manufacturing flatsawn than when manufacturing quartersawn.

When manufacturing flatsawn lumber, the yield of lumber from a log can be several percent to as much as 20% higher than when manufacturing quartersawn. Flatsawing requires less technical and mechanical effort than quartersawing. Flatsawn lumber is prone to cupping in drying. Quartersawn lumber is prone to side bend in drying. Quartersawn wears better when used as a flooring material than flatsawn. Flatsawn lumber, especially oak, is subject to surface checking, honeycomb (interior checks) and splitting (especially end splits) in drying, while quartersawn is not. Flatsawn lumber dries up to 15% faster than quartersawn. Quartersawn lumber will accentuate other grain patterns such as wavy grain and interlocked grain.

From contributor B:

This is very good and supports Gene’s descriptions of where the rift and quartered boards are actually coming from (I was wrong). I'm right though as to the selection of rift over quartered oak to minimize ray fleck. What can I say: "You're never too old to learn something new (or make a fool of yourself).

From contributor B:

Please tell me if this sounds right. There are three ways to render a log into usable lumber, namely: rift sawn, quartersawn and plain sawn. These terms describe the particular method the sawmill has used to slice up the log but not to grade the individual boards, correct? A rift sawn log is cut radially. A quartersawn log is first quartered before being sawn into boards. A plain sawn log is a series of parallel cuts.

Grading: A rift sawn log yields individual boards which are graded as quartersawn lumber (what?). A quartersawn log yields both quartersawn and rift sawn lumber. A plain sawn log will yield all lumber grades.

From the original questioner:

As confusing as it seems, I would agree with your assessment. The name of the process apparently does not necessarily indicate the name of the end product. Thanks again to you and Gene for all of your input. On the practical side, I have a sample of rift red oak veneer which I am going to try the finish on.

From Gene Wengert, forum technical advisor:

The information about sawing techniques is not correct. For a hardwood log, the log can be live sawn (also rarely through and through sawing), cant sawn (where a tie comes out of the center oftentimes) or grade sawn (also rarely called sawing around). In addition, a log can be quartersawn using several different techniques. The one referred to as rift sawn in previous discussion is incorrectly named. That is, it is a quarter sawing method. A log does not need to be quartered in order to produce quartered lumber. Log diameter is a major factor in determining the precise sawing technique for producing quarter lumber. The equipment at the mill also has an effect.

If anyone would like more info on the various quarter sawing techniques, check “Sawing, Drying, and Edging Hardwood.” The amount of quartersawn lumber that is sawn depends on the operator mainly and the precise technique used. We also have some pictures in the archives.

A quartersawn log can produce almost all quarter lumber. It’s incorrect to say that a plain sawn yields all grades, as we are not talking about grades but about grain. Plain sawn as referenced earlier in a posting is actually rarely used in hardwood sawing. Due to the low grade of wood near the center of a log, live sawing (the correct name, as I stated earlier) will produce low grade quarter and rift pieces, so it is not used in practice, unless producing pallet lumber or No. 3 common for flooring.