Fine Points of Architectural Door Construction

Here is a thoroughly professional discussion of the pros and cons of "engineered" door construction, along with a conversation about springing or crowning doors for a snug closure. September 7, 2013

Question

I have made a couple of doors using solid stock but now I want to make some using made up stiles. What would be the process in making up these stiles and what would be the best core material to use?

Forum Responses

(Architectural Woodworking Forum)

From contributor S:

The term stile typically refers to the long vertical parts of the frame on a frame and panel door. I think you might be referring to the panel? Are these cabinet doors or entry doors?

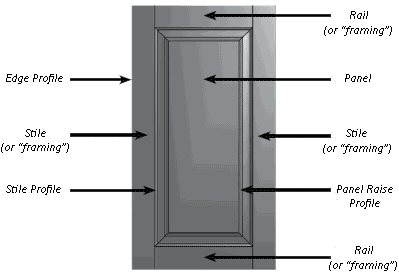

Click here for higher quality, full size image

From the original questioner:

These are interior entry doors 3-0 x 7-0 1 3/4 thick. We do mainly commercial work so these doors would be the entrance a lawyer’s office or a corporate suite. These doors are not exterior but are the entrance doors to a company’s office.

From contributor F:

A link to the Knowledge Base is below and if you browse you will find some discussion on this that may help you out. Also, there are companies out there specializing in making the parts you’re looking for, which happen to be called stave core.

Knowledge Base

From contributor G:

The process is plane stock to thickness, rip to desired width (thickness of door plus cleanup allowance minus door skin thickness x 2) and then lam up into wide pieces and plane to thickness. Rip pieces off of these lamination's the width of your style minus solid on edges for profile. Joint and lam on solid edges of the species you’re using for faces. Clean this up on the faces and lam on face veneer (.0625 to .1875 thick). Clean up the edges and you are ready to build your door. As for the best material, pine is often used because of the strength to weight ratio but any stable dry wood is a good choice. I shy away from yellow poplar because of issues I have had with it in the past, but once it is lammed up it should not be a problem. As you can see the labor factor is high on this type of construction so I only use it if I can't get good 8/4 stock.

From contributor M:

Engineered stiles are made from solid wood fingerjoint, lvl, timberstrand and in some cases even particleboard core. Some folks even make their own by laminating full length poplar rips. There are plus and minuses to all of them but for us the most consistent and stable end product for both interior and exterior is the solid wood fingerjointed core with solid wood edges and a heavy face lamination.

As for your doors, you can outsource the complete stile, you can outsource just the core, or you can start from scratch. We sell a lot of fingerjoint slabs for guys just like you who then rip it to the widths that best suit the door project at hand. They are available from other sources of course. I would stay away from any lvl type core products because they can cause some grief when any type of moisture is reintroduced, even on interior doors.

From Contributor O:

I am a fan of solid stiles, either one piece or laminated for thickness. I would use engineered only if limited materials or very large sizes makes it impossible to do them in solid. Know your lumber and your vendor and use the best wood you can find. Own, operate, and correctly use a proper jointer and planer and there will be no problems.

Be assured there is precious little engineering going into the aforementioned type of construction. More properly they are cost accounted stiles since I believe that is the primary driver behind their use. I admit they do add some stability, but joint telegraphing, failed glue lines, rot resistance and veneer sand-throughs are all real problems solid stiles do not have. Built up stiles (a more accurate name) have more parts, so more pieces to make and to glue together with much higher labor input.

From contributor M:

Contributor O I have to respectfully disagree on a couple of points. I don't want to contest the craftsmanship it takes to work solid material into a perfectly flat usable product especially in wide thick products like a door stile, because it is an art. However if you had any opportunity to see the talents and skills of the people performing the many different operations required to make a good engineered door component I think you may feel it is an art in itself.

First, the notion using engineered stiles and rails are in any way a cheap way out is quite the contrary. In fact our benchmark wood species we use as a tradeoff is cherry, meaning we can actually save money going engineered when the cost per board foot reaches approximately what good cherry is. Please don't categorize all engineered door parts together, we are not talking box store doors with micro thin veneers on press board core.

Secondly, as for solid versus engineered let’s just say we don't and won't produce a single door, interior or exterior, regardless of what species that isn't on an engineered stile and rail. Solid wood in any fashion has exponentially increased chance for warping and I don't care how good your technique and or your lumber selection is. It is just a matter of how you want to hedge your bets. Call backs are very expensive for everyone and the end result is the contractor and customer soon forget you gave them solid wood doors when they don't perform. Interestingly enough I have never had a client decline our doors because we use engineered components after explaining the benefits and show how the parts are actually produced.

From Contributor O:

To contributor M: I do have a real problem with the term and the implication of technical superiority it imparts where there likely is no justification. I am sure you make a good product and your people are nice folks and capable craftsmen that care about their work. I choose to uphold the craftsmanship end of the activity, for whatever reasons I may have - real or imagined. Not everyone wants, understands or cares about that, and that is fine. Our doors certainly are not for everyone. With over 40 years of building doors and 23 as a business owner, I have been responsible for thousands of doors. Any woodworker can count the number of doors I have had problems with - warping being the most prominent. Some were even our fault - wet wood being the culprit.

From contributor S:

I think Contributor O has a point. There is very little engineering going into these materials. The term is a little disingenuous. I think the term originates from the construction industry where engineered lumber or beams are actually engineered and certified by a real engineer. I used to order custom engineered beams for remodeling projects all the time. I do not think finger jointed/glued up lumber is engineered the same way. Like Contributor O said engineered stiles are a cost driven product, engineered beams are an engineering driven product.

I am not a door manufacturer - I probably make ten a year but I do not like using engineered stiles. Having to center the rip cuts so there is not a sliver left on the outside, the telegraphing, and joinery are issues for me. I would use engineered stiles if I was making doors for a living.

From Contributor O:

No offense taken here, and I should mention I certainly respect any professional's efforts at making a product and a go of it in this world. Fortunately, this is a big world and there is plenty of room for differences. Well thought out plans/methods by reasonable people with correct intentions are worthy of respect and consideration.

We each have our opinions, and there is no definitive right or wrong. The real difference between our products in real world experience is probably minimal. I am an unrepentant romantic, and admit to being attracted to using the solid wood as a more pure process.

I have used stave built or assembled stiles for a few things over the years. A dramatic pair of 11' Wenge doors just wanted to eat up way too much beautiful quartered stock to do them in solid, so the core was in pine. Once they were built I appreciated the weight reduction afforded by the pine. I noted that my material cost savings was almost equally offset by the higher labor.

From Contributor E:

To contributor O: I'm glad to hear you say there is no right or wrong in this area, because I am of the opinion that the stave core stile is the way to go. I too have built a few solid wood stile doors, although not many over 7' tall because of what it takes to get the lumber flat before planing to thickness. When I have a call to build doors now, it's always with a stave core construction for my stiles and solids for my rails.

I saw my own skins as well as gluing up my core, use West epoxy for gluing the skins to the cores (without excessive pressure so as to starve the joint) and those bad boys stay as flat and straight as you would ever want. It certainly costs me more in labor, but they sure do stay straight after they leave the shop. There are many ways to skin a cat, and I have just found that it works a little better for me, just as I accept the fact your solid wood stiles work best for you.

From Contributor O:

Contributor E - I have a decent joiner and use it to straighten and square stock, face and edge, then plane S4S. On the occasions where I made stave core stiles I still used the joiner to straighten the edge banded core blanks, then S4S, then faced with skins. The joiner controlled the flatness throughout. So the joiner plays an important role. For those of us that like to put a little spring in the latch stiles, it is a necessity.

From contributor Y:

When you say "put a little spring in the latch styles" how much spring are you talking about? Do you do this with a jointer that has the ability to can't the tables to make the slightly concave cut in the latch style? Is there a way to do this on a jointer that does not have the ability to easily tilt the tables then return them to a nice flat calibrated state?

From Contributor O:

I like about 1/8" to 3/16" in a 2-1/4" x 8' door that is to be hung in a solid jamb without compressible foam weatherstrip. I do it on a conventional joiner since I don't have a patternmaker's joiner. It just takes a bit of fiddling and eyeballing. Paired hinged doors will also get a bit of spring, but in opposite directions.

From the original questioner:

Can you show by a drawing how you put spring in the stiles?

From Contributor O:

To the original questioner: Spend some time with your joiner and a scrap stile and you can figure it out. I typically do it with light cuts - less than 1/16" after flattening. Work each end with partial cuts, about 1/5 the length, then 1/3 the length with the bow or hollow up on the joiner. Planing then repeats the hollow. Remember the joiner is not usually a finishing machine, so you need enough wood left to plane the jointed faces.

The purpose of the sprung stile is to seal the door and tension the latch. The latch stile will contact the solid jamb at top and bottom and then spring to hold the latch. It keeps the door tight, prevents rattles at the latch and the jamb and reads as solid to those using the door.

This is a good reason to argue for supplying a frame and pre-hanging to your customer, in lieu of a door only. This will also help you distinguish yourself.

From contributor M:

So all this time my bowed solid wood stiles simply had latch spring, and I could have up-charged? Pure genius! There is a lesson for all door hangers in there. If you happen to be hanging lesser doors, a good look at how they are bowed and hinge appropriately will help get the job done.

From Contributor O:

All the older carpenters I know know to crown a door when they fit and hang. Most of the younger ones have never heard of it, but also don't hang doors - they come that way. Mill men exhibit the same loss of knowledge. Nearly everyone thinks it is way too much trouble. I use it to help distinguish our work from that of others and to demonstrate the depth of knowledge - that we consider the context of the door, not just the door alone.

In training various shop hands over the years it was always a struggle to get them to understand that everything had to be dead straight except for the things we didn't want straight, and then they had to be bowed just right!

Actually, I think “know how” is a major selling point that a lot of us ignore. The outside world has little knowledge of what we know, or why we do things a certain way. Being able to demonstrate a properly hung and sprung door is a joy and eye-opener. Once a potential customer sees it and learns the why, they really get it, and become a loyal customer.

We had 8' tall 1-3/4 Brazilian cherry rest room doors in my last big shop - heavy. Each was sprung in a solid jamb, four ball bearing 4x4 hinges with a privacy latch. Nearly everyone commented on how nice these big, heavy and secure doors were, and the pleasant sound they made when closed and latched. Many visitors had never been around premium doors, and these helped sell more than one job. One lady asked "Can I have doors like that?!" You certainly can.

From contributor S:

I have to confess my ignorance here. In regards to "latch spring" which way is it bowed, and what is the purpose?

From contributor Y:

I will take a shot at explaining. The style with the spring in it would be a latch side style with a slight bow that would allow the top of the door and the bottom of the door to touch the stops on the jambs just before the latch latched. This is so there would be a little pressure on the latch when the door is closed and would prevent the door from wiggling when closed. There may be other benefits too, as a new millworker that is my guess.

From contributor H:

It's basic woodworking to crown door parts to the hinge - latch side, even

cabinet doors. The benefits are obvious, the top and bottom hit the stops first making a solid close and as Contributor O points out better compression against the gaskets. My experience has been most door stiles over 7 1/2' tall usually have a slight crown of 1/16 or so even with meticulous facing and planing of the parts.

When making 3" thick doors out of good quartered material it is sometimes hard to determine crown on 8' plus stiles. I would never purposely joint a crown into one of my stiles. Wood is a living material and moves, especially when stacked on carts overnight. If you want a test of how tight your door or window fits to the gaskets take a piece of typing paper closed in the door and try to move it. See the image below. It should not move in any location on the door edges, tops and bottoms.

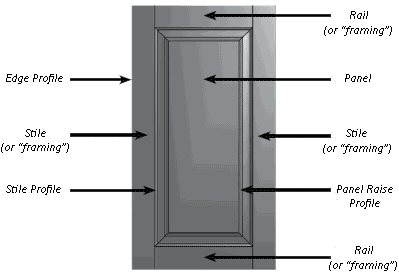

Click here for full size image

From Contributor O:

Contributor Y you have it right. As Contributor H explains it is basic woodworking to crown stiles, and for the purposes he states. This is so basic to my work that I often overlook it in discussions with others about the work.

We do have to crown our 10/4 and 8/4 mahogany stiles since they stay so dang straight on their own, but oak and cherry and pine, etc. all will usually show a crown after a day or two. So if there is a bow in a stile - unavoidable in some cases. Is there a better way to position it in the door? Turn the lemon into an asset, and let it work for you.

We like to rough rip and rough length, let the wood relax a day or two, face and edge, and then plane to dimension. The stiles are all paired at layout and the better crowns are utilized for latch stiles. The hinges will take out any slight bow on the hinge stile. If we are doing doors only, with no hanging, the doors are still crowned and we try to mention this to the installation carpenters.

From contributor Y:

Thanks for the clarification. For further clarification, is crowning something to look for when making multi point locking doors and windows? It certainly seems like it would be beneficial for casement windows to get a good seal.

From contributor H:

I did mention it when we mark the parts with the triangle. I realize now we need to spend more time with this. We do the same for all multipoint doors and windows. They are a little more forgiving but still need to be close. Rosenheim standards say the parts cannot have more than 1.5mm bow in length.

From contributor D:

I admit to hanging a few doors with a slight bow, but only singles. Double doors I wouldn't try that on though. I've looked on with some interest on the solid stiles thing, but personally I am not sold. Some of us have much better environmental control, from storage all the way to finishing. Others who sell doors unfinished and to contractors who aren't so diligent in their sealing I'm sure will suffer the consequences. I wouldn't feel comfortable one bit advocating solid stiles just for these reasons - not by the way because of possible use of lesser grades of lumber.

I'm sure pattern grade Honduras would be much nicer to use all the time, if only for its consistency, but all wood moves and their volumetric expansion rates are well documented by species and moisture percentage. Some of us farther down the food chain also won't have customers willing to pay for twice or three times as much material cost. Stave core stiles are still the industry standard, not for costs up front, but for added insurance to combat warp. Also, it gives me great pleasure to bookmatch veneers on high end units, something that literally takes my breath away at the end result, even after having built thousands of doors.

From contributor F:

Contributor D are you making your own stave cores? When I priced them out from a certain NY manufacturer it was more expensive than using solid wood! Understand I'm not taking sides on this one as I think both ways have their merits. I just found in my experience there was nothing to be saved as far as materials are concerned by going to a stave core. So I'm curious if you’re making your own and if not where you’re sourcing them from.

From contributor D:

I make them in house. In the past outsourcing was the way to go until you're well enough equipped. RF press, straight line rip, orbital frame/veneer saw and batch processing pretty much make or break the deal.

From contributor L:

I just checked my AWI book and they allow all the methods for frame construction. The trick is moisture control. For premium work they require veneered panels, flat or raised. Veneers for the frames need to be 1/16" plus after sanding. Most of the doors we make now are for offices where the veneers need to be a good match to the rest of the woodwork so we re-saw them from the same stock. With the proper equipment it's not all that hard to make stave core doors. It is more expensive.

We used to make a lot of interior doors both in stave core and solid lumber. We tended to have problems with 1 3/4" oak doors so they were almost always made stave. Poor control of the kiln drying. Often, when checked, the center of 8/4 was wetter than the outside. Then there is the issue of honey comb. Probably due to mixed thickness kiln loads.

I understand the idea of putting some curve into the stiles so they contact top and bottom and "tension" the latch. As a practical matter I don't see that it matters. Most door stops are fastened on with finish nails. A few good slams and it self-adjusts. Some architects specify T and G stop let into the jamb. The groove is made larger than the tongue so the stop can be adjusted to the door. It’s easily done it just takes a few minutes extra on the molder setup.