Antique Machinery and Stair Rail Fabrication

The old machinery is cool, but it can't compete with modern CNC equipment for productivity (or safety). October 19, 2013

Question

(WOODWEB Member) :

I'm looking for recommendations for advanced, in-depth woodworking machinery books regarding the use and maintenances of large 36" (high speed) bandsaws, jointers (8-16"), and shapers. My jointer has a row of small taped screw holes on the outfeed table parallel to the rebate ledge and a ways away. What were these used for? Kind of like being able to add an outside fence.

Forum Responses

(Architectural Woodworking Forum)

From contributor R:

What's the brand, width and age of your jointer?

From the original questioner:

Thanks, did not think the screw holes being parallel to the rebate ledge was unique to my jointer. Power (L. Power?), 16", direct drive 3 hp., three knife, three legs, 8' table (?), outfeed table is wide (20"+?). From naval ship yard along with high speed Moak 36" bandsaw.

From contributor M:

No books like that around. There is a book on band saws and another about wood shop machines in general. Check Taunton press. But these are not really all that in depth.

From contributor D:

Two places to start are Linden Publishing's woodworkerslibrary.com and CGG Schmidt's bookshelf. There is not a lot in the few books that exist on old line millwork. The old guys that taught me 40 years ago were not formally educated and the industry seemed to be that way throughout. It was all taught verbally once you got beyond high school shop.

From contributor E:

I don't know about the books, but if you can't find them it really won't matter anyway. Truth be told the computer you're using to ask here is far more powerful these days and holds more info than any library. Nothing against books, just saying that for what you're looking for, there are alternatives. For your older machinery I highly recommend joining OWWM.org as repair and maintenance of older equipment is the specialty over there.

From contributor D:

It is the advanced techniques that you will have a hard time finding out about - especially on the shapers. The older shaper books will help, but you will have to add guards and methods that will protect the operator. Some of that old work was treacherous, to say the least. "Real men only have 8 fingers" is not a viable work ethic today. As for maintenance, "grease 'em on your birthday" is what I always was told. But contributor J is right, the OWWM site is a great resource.

From the original questioner:

Thanks. I have the "Shaper Handbook" by Eric Stephenson, and I do refer to the later chapters.

The shops I worked out of were not too keen on me learning too much and I've read and heard a lot of scary stories about the shaper! The problem is I need to shape handrail and stair parts. Probably will be making a bed saddle and loosing the belt some and taking small cuts.

From contributor D:

Stair rail parts are very dangerous work if you are unsure, and still forbidding if you know what you are doing. I make more parts with a router and a lathe than I do a shaper. I would never get near a shaper with a volute. Those require double spindles and counter rotating tooling to do correctly, and then they will only remove the forearm or less. Seriously, this is not something to do unless you have someone guide you through it step by step and all other things are in alignment. Sub it out or turn it down - far better in the long run.

From contributor P:

Eric Stephenson's "Spindle Moulder Handbook," purchased from Charles GG Schmidt & Co. Only book I ever found that covers advanced techniques.

From the original questioner:

Contributor D, very good advice! Problem is I need and want to be able to do this. Doing the shaping by hand takes awhile, and I just want to speed it up a little. Not planning to mass produce. Being a stair builder is one of the few things I'm good at and I need to be better than my competition.

I'm very impressed by contributor J. My work goes for many dollars less and I need to turn my jobs over fairly quickly.

From the original questioner:

I really think this is an area where the CNC router has changed everything. It simply is not worth it anymore to spend the time and effort to build the jigs and set up the complex blanks that allow complicated stair parts. Even my most old school suppliers have switched to CNC. There are amazing programs developed just for moulding and stair parts. Even a 3 axis machine can do the job in most cases.

In my opinion you are overly fixated on learning techniques that are not as valuable as you believe them to be. I will hire a millwright with advanced CNC knowledge over an advanced shaper operator anyway. Few shops will even allow those older techniques nowadays, and for good reason.

From contributor D:

Contributor J sells for the right price, or a bit lower than it should be. If you are trying to produce a similar product for less money, you will not succeed. This type of work is very expensive, as it should be. A custom stair should exhibit exceptional craftsmanship, and the cost will reflect that.

The fact that the work is expensive and dangerous for a one-off or small numbers does not go away when one needs to turn jobs fairly quickly. I may be presuming too much, but you need to go back to Business 101 and look at costs. It is not your job to provide products like this at discounts. You will fail. Don't think you aren't the first one to tread this path - many others have gone before you, and you can benefit from their experiences.

I agree about the CNC, and I am not a fan. But in the case of stair part fittings, the CNC is probably the near perfect solution.

From the original questioner:

Thanks guys, I'm in complete agreement! I do not work on the kind of stairs Mr. Baldwin does - those kind of stairs are just a dream for me. The shops I worked for let others, the in crowd, do the nice stuff. From time-to-time I would get to work in a multi-million dollar mansion, not often enough for me.

Shortly after I went off on my own I priced my work right up there with the expensive shop and I planned to compete (and have) with them. Whoever is doing the upscale market is traveling in and working for less. There have been bids barely over the cost of materials! We've been around a long time and stand behind our work but still get outbid.

Years ago you would run into contractors and builders that knew what they were doing! There has been an influx of people with money (or off shore backing) that have a different mindset.

From contributor J:

The shaper is a great machine and stair parts and railings can still be done with relative safety, but the learning curve can be cruel.

As for pricing and custom work, I have to earn enough to make up for zero production orders (and it's almost never enough). Since I don't contract or build stairs anymore, all I've become is a minor supplier (which should not be an enviable position by anyone's estimation). I also have to compete with fully equipped CNC and robotic manufacturing, which was certainly not a factor 30 years ago.

When you set up to do something, it really needs to be safe enough for your own child to operate. This is nearly impossible with old-school technology and methods (and there never was any "school" to begin with).

I don't usually offer advice or specific information with regard to milling and shaping, since some of what I do is outdated and a bit dangerous. I will however speak out with regard to safety and caution. If I was forced to go back to Grandpa's old shaper and home-ground shaper knives... I would run for the back door.

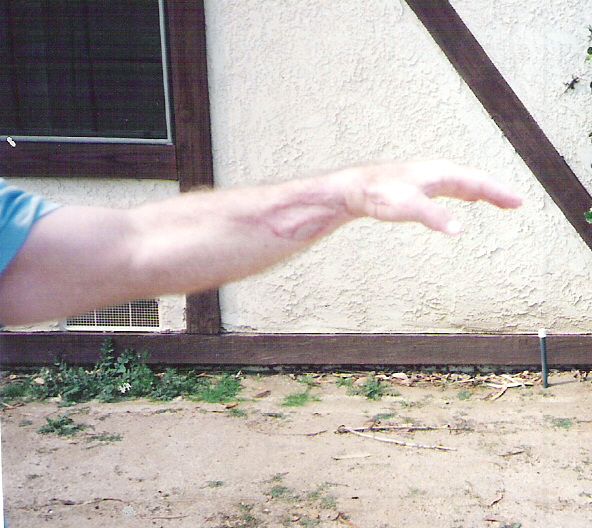

This nasty scar on my forearm is actually the source of the skin-graft used to close the wound and missing parts of the base of my thumb (splattered on the wall). This was about 20 years ago but still a vivid reminder of a momentary lapse of judgment. I'm not proud of this - I'm embarrassed.

I'm sharing this because it might be the most important thing I could ever share on WOODWEB. It's okay to love your work and have sawdust in your blood but certainly, not the other way round.

Click here for higher quality, larger image

From the original questioner:

I have the greatest respect for you and your skill. Being a better stairbuilder is something I've wanted to do for years and it may be one of the few things I'm fairly good at. I've bought a lot of stuff over the years for shaping rail (bandsaw). Many, many years ago, I would have loved to work with you. I'm still working partly because the union does not think they need to pay my retirement.

Regarding the bandsaw; I emailed Northfield and they replied they have never done anything like that.

Going to the Naval yard was a trip! One bandsaw had its lower wheel in the basement and the upper wheel a floor above the main floor. On the main floor, where my soon to be jointer and bandsaw (small) waited for me, you did not see the wheels - only the blades and the ceiling were warehouse high.

In another warehouse, about the size of a football field, there were more Yates-American Y-36 bandsaws than you could count. Maybe two-three 30" bandsaws (Oliver?) And a couple of Y-36's for plastic (these were froze-up). Interesting thing, some saws had a raised-foot platform (4-6") and at least one Y-36 was sunk about 4-6" into concrete (the mover was not very happy with me!). Almost all the saws had a wood handle out past the table for changing the angle (maybe while it was running). Does anyone need a Y-36 with the lower door cut off (about 6")?

From contributor N:

Those old Yates were for sawing ship's frames. The frames were sawn with a constantly changing angle - the guy feeding the frame would call out the angle to another guy controlling the table, usually several feet away. Door cut-outs were for easier dust evacuation. On really large frames the beveling was done afterwards. Traditional wooden boatbuilding is a dying art, and no longer done in modern production. Only hobbyists and one-off custom builders keep it alive. Someone over on the woodenboat forum will probably be interested in the machinery over at the naval shipyard.

From the original questioner:

These bandsaws were the standard issue upright. They had a regular tilt table, the lock was not used and a handle (about 3') was under the table. And yes, a second person could use this handle to change the angle. It also made changing the table angle a lot easier.

There also was an interesting Orin machine about the size of a double shaper, with a tilting cutter head. The cutter head was at a 90 degree to the table and exposed, like a 12" jointer on its side. You could run some heavy stuff through it and bevel the side. If you think a shaper cutter is scary, try a 12" exposed jointer cutter!

From contributor D:

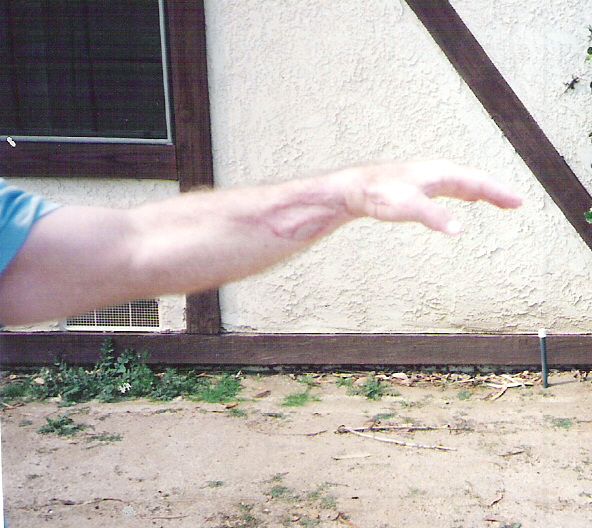

Off topic, but here is a lathe that will turn trees into sailing masts. It is a tracer lathe, largest in North America.

Click here for higher quality, larger image

Editor's Note: If you need machinery from the best European brands, use Martin Woodworking (website).