Clamping Lock Miters

Other Versions

Spanish

A discussion of the fine points of aligning, clamping, and gluing miter joints, with some commentary on whether lock miters are even worth the trouble. June 3, 2013

Question

We have a pretty decent setup for running lock miters on our shaper. The only thing I am not getting is how to go about the clamping. It is my understanding that you should be able to clamp in just one direction to get a super tight clean joint. What ends up happening is we have to clamp in both directions and it becomes a little awkward and defeats the purpose. Could it be I need to go with some different tooling? We are using Feud tooling. In the near future thinking of going with an Amana inset tooling head so we don't have problems with sharpening.

Forum Responses

(Cabinetmaking Forum)

From contributor M:

You must be running your boards with opposing profiles, so that you have to clamp all the way around rather than just on two faces.

I do a fair amount of lock miter and we run the same profile on both sides of two boards and the opposing profile on both sides of the other two boards. This allows you to have, I guess you could say, two sides and a top and bottom if you think of the box on its side.

From contributor M:

To clarify, are you running one edge of all boards vertically and the other edge of the same board flat? We run two boards both edges on the flat (face against table), and the other two both edges run vertical (face against fence).

From the original questioner:

We are just doing one miter at a time, mostly for our finished end panels. I think you may be thinking for a 4 sided post? Although sometimes we do columns this way so the face board has the same profile on both sides the flanking boards have the opposite profile. Still having to clamp both directions in the column situation.

From contributor M:

I guess I'm not understanding the both directions issue. To me, it's the same regardless. While in some instances we have to stick a clamp in to close the joint a little, I am just clamping in the direction of the tongue in the joint.

From the original questioner:

I guess the biggest issue is that we should be able to clamp in one direction but the miter slips, so we have to clamp the other direction to compensate. Could it be the tooling we have is too sloppy?

From contributor M:

It would seem like there is something going on with a bit of loose fit. I can honestly say that perhaps 10% of the lock miters we do are sweet right out of the gate. Most of them need a little tweaking and fussing, but I have always had success clamping with the tongue and the occasional clamp in the other direction for a stubborn spot. We are running an 1 1/4 bore Freud cutter as well.

From contributor C:

We used to run them at one of the shops I worked with years ago with what is posted on Freud's site. However, the trick we found was using the biggest most massive power feeder we had was what it took to make sure we got it to be flat. And we had beefed up the fence quite a bit. After running, glued and pinned or Senclamped the ends. Only one clamp needed, also, because the one run of the profile prohibited the other from moving.

From contributor R:

We used to use a Scotch/3M #355 tape to do all our v-folding and end panel applications. It does not stretch and has very good bonding to whatever you adhere it to. Simply put a couple of strips across the joint to bring it together, then a long strip or strips straight down the joint, flip the wood over, put glue in the V and fold, clamp a small 90 degree corner block on each end of the panel and let it dry. You will be amazed how good this works. When you take the tape off, use naphtha to dissolve the adhesive on the glue. Naphtha won't affect the finish and it keeps you from pulling the grain off the wood.

From contributor J:

Another alternative may be to lose the lock miter altogether. Seems like it's probably overkill for a finished panel? I do my panels with a simple 45 cut, yellow glue, and blue tape to clamp it up. Goes fast and easy and alignment is pretty foolproof.

From contributor I:

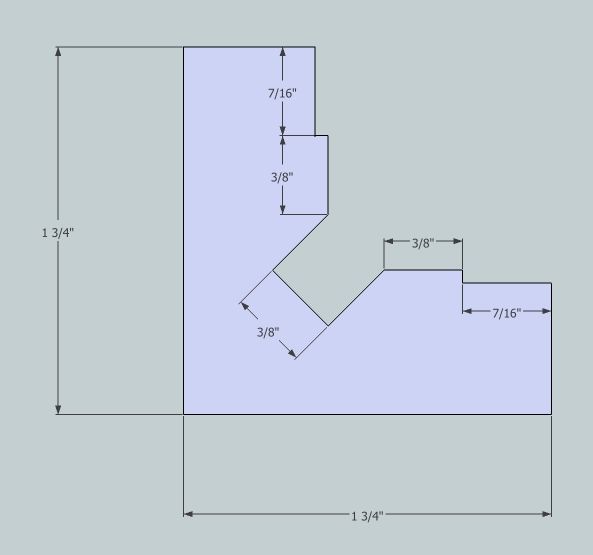

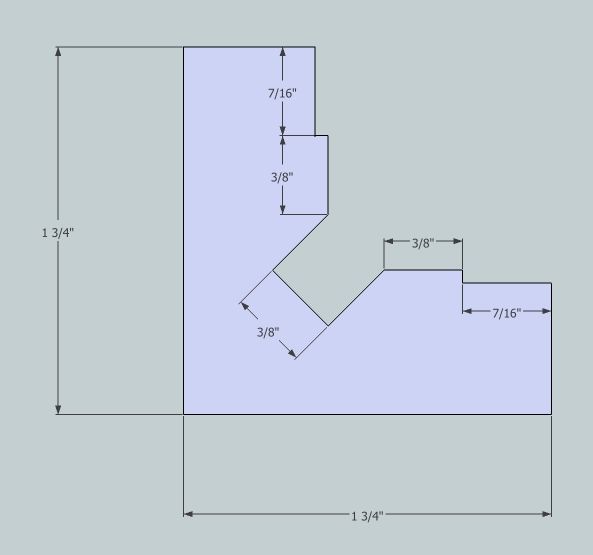

I had to glue up a lot of bases for exhibit cases which used lock miter joints. I ended up making some clamping cauls with the cross-section shown below. The cauls were approximately the length of the sides. I clamped the joint from both directions. I first clamped the bases in the direction of the tongues, and then added clamps in the other direction. The disadvantage to this system is that you can't see the joint after you clamp it. However, the joints pulled together well, and I didn't have many problems.

Click here for higher quality, full size image

From contributor N:

I also use a lock miter for finished ends. I find that it makes gluing up a lot easier, because it aligns itself. I use an Amana bit, with a heavy duty Martin shaper and feeder. A good shaper/power feeder is a must, especially for tall cabinets where you have a long end panel and face frame to deal with. I run the end panels flat on the table, and the face frame material against the fence, then clamp along the end panel side.

From contributor A:

I'm with contributor J on this one. Rip them 45 on the TS. Just high quality strong 3M clear packing tape. Miter fold them with a bit of glue. They often come out better with less damage than running them through the shaper. I stopped using the lock miter cutters years ago, out of frustration.

From contributor D:

I have to side with the simple miter guys. We do hundreds if not thousands of feet of miters a year; face frames to end panels, columns, countertops, etc. Nothing we've found is better than a ripped joint on the tablesaw miter folded with tape. We once had an elaborate setup with shaper, powerfeeder, jigs and a 6" diameter lock miter cutter. Simple is better. For anything that isn't practical to run through the tablesaw, we use a

Festool with a 10' track.

From contributor N:

I think it just comes down to your equipment. My shaper is all computerized, so for me it is just as easy to run a lock miter as it is to run a simple 45 degree cutter. That said, the lock miter goes together a lot easier once it's properly machined. If I was using old school equipment though, I probably wouldn't use lock miters.

From contributor A:

There are two styles of lock miter cutters. With one style, you run one edge flat on the table and the other edge vertical against the fence. The other style you run both flat on the table. You then take one side of the miter and run it flat on the tablesaw with a 1/4" dado to remove the tongue and to put a groove into the lock miter. The second style is what we use where I work. It is very easy to work with and make really nice miters. We clamp in one direction. The tighter you make the clamp, the tighter the miter becomes.

From contributor B:

Do you use special material outfeed fence supports on your shaper and saw when using your type lock miter cutters?

From contributor A:

I'm not exactly sure what you mean, but the only thing we use is a piece of plywood on the shaper table top. Because the shaper doesn't run in reverse, we have to run the parts face down. The plywood raises the part up so the point of the lock miter rides against the fence and not under it. The table saw doesn't require anything special. If you can set up a power feeder on the saw, that helps give a consistent dado.

From contributor B:

I hand-fed my parts so had to add a guide to the fence so the tongue just shaped registered against the guide instead of the sharp corner that was so thin it crumpled under pressure against the regular fence because of being hand fed I suppose. Same for the table saw that cut the 1/4" dado - the same sharp corner had to be kept away from the fence, infeed and outfeed, so another guide mounted on the fence that registered on a more solid part of the miter cut.

From contributor O:

I agree with both opinions. We use the simple table saw miter and tape joints on panel ends, etc. For pre-hung casing out of solid wood, hard to beat the speed and accuracy of the lock miter.

Here are a couple of things to keep in mind that I have done over the years to make it work best. If you use your standard split shaper fences as the guides, you will always fight some amount of out of parallel. I use a laminated 90 degree fence with a zero clearance or close to zero clearance cutout for the lock miter. This lets us do safe manual set up for hand feeding so you can get the flat and upright cuts as near perfect as possible. Then we have 2 feeders set up on the shaper. One for the vertical and one for the flat. We run all the flat then flip for the vertical. We then set up horses and usually glue about 6 to 8 pieces together at once. The jamb lays flat and the casing is vertical. We use some jointed boards for the clamps to press against and for 8 to 10 foot stock usually use about 6 clamps. Two guys set them against the wall to cure and lay up another set.