Reprinted with permission from Modern Woodworking.

Custom furniture maker relies on four-step process including models, drawings, layouts and tests

By Brooke Baldwin

Determine the order of construction for laying out and cutting accurate joinery, while maintaining reference lines for the shaping of each piece. That’s the formula David Fay of David Fay Custom Furniture in Oakland, Calif., uses in building each of his custom furniture projects.

The size and proportions of the posts and rails change from one end to the other on this commissioned bed frame.

Designing every piece he makes for his customers specifically for their needs and aesthetics, Fay considers himself “more of a physical designer than a theoretical designer. Since I don’t have the luxury of a prototype for each piece, I do try to learn as much as I can from full scale design work,” he says. Fay has created this four-step process to develop and articulate his designs:

1. Make a “Quick” full-scale model. “I make a full-scale model to visually see and react to my design idea. I spend usually less than two hours to mock up my idea. This step lacks refinement, but is useful to evaluate the success of the initial inspiration. It is also useful to show potential customers what they otherwise may not have been able to visualize.

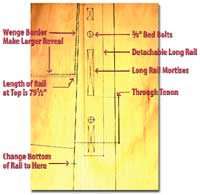

2. Make a full-scale drawing. “A full-scale drawing on one-fourth-inch particle board helps me get beyond my sketches and initial model. This is the time to analyze the structural needs and lay out the proportions that lead to the desired visual aesthetic. I am constantly making subtle variations to the joinery and proportions of each member once I draw it out in full scale.

3. Lay out joinery and shaping, cut joints, then shape piece. “I lay out all the joinery and shaping for each piece before I cut anything. This allows me to consider how best to cut the joinery, examine design proportions and mark my reference lines for each piece before actually making any cuts.

4. Make a test piece. “I almost always make an extra leg or post or intersection of my designs. Each test piece is extremely useful as a visual and tactile reference. It gives me more information than any drawing and allows customers to see and feel the woods and shapes of past designs.”

Inspiration comes from many sources

With a background in building post and beam timberframe homes in which posts, beams and rafters are connected only with mortise and tenon joints, Fay now builds furniture like those houses. “That was my introduction to mortise and tenon joinery, Japanese hand tools and beautiful natural materials,” he says. “I then took furniture-making classes and they steered my interest to a smaller scale, for which I believe I am better suited. I started doing furniture projects for friends and family and then branched out and got my own shop where I do all custom furniture.”

This detail of a full scale drawing enables the specifics of joinery and design to be articulated, thus making it a useful and decisive tool for design.

Fay says his own inspiration comes from the arts and crafts movement along with the minimalism found in Shaker and Japanese design. “Although I am not directly taking those designs, I would say that my furniture designs match those design aesthetics.

“People who are drawn to me are people who enjoy the process of developing a design from scratch. Even if clients say they want a particular bookcase or bed frame that I have already designed, we’ll still discuss materials, proportions and variations so that they are playing a part in its development.”

Before designing a particular bed frame, Fay discovered that his clients were interested in bridge designs by Swiss bridge engineer and architect, Robert Maillart. “They wanted the bed frame design to express the structural elements of the mortise and tenon joinery as an integral part of the design,” he says. “They also wanted to allow the changing shapes of each piece in the frame to reflect the structural requirements. This is not to say that this is a bridge bed frame, but it is a bed frame inspired by a bridge and an architect.” The bed frame was made from Honduran mahogany (frame), African mahogany (panels and wenge wood (pegs and border detail). Its dimensions were 86” long by 82” wide by 43” high.

Fay says fifty percent of his work over the last four years is from second, third and fourth time customers. Since he is a one-man shop, he says there really is never an increase in growth — “just more work coming up.” Turnaround time is from six to eight months. “Doing custom work and developing something from scratch is inherently labor intensive — every step of the process,” he says. “It takes me a long time, so that makes it expensive. On top of that, there is a lot of back and forth contact with the customer. It really does come down to a relationship.”

Fay selects various hardwoods for his furniture, depending on the project. “If someone wants a dining table out of solid wood, for example, I need to find pieces that are wide enough for the project,” he notes. “A lot of the woods that I have gotten over the years are from EcoTimber, a company that deals with sustainable harvested wood.

“I’ve got some gorgeous tools in my shop — a 16” Northfield jointer, a 16” Northfield table saw, a 14” Oliver table saw, a 18” Oliver planer, and a bandsaw, drill press, mortising machine, disc sander and table sander. Using quality machinery helps mill accurate work, but the ease of its construction relies on a careful consideration of the whole process. Understanding this process and maintaining a point of reference allows work to ultimately be done more efficiently and accurately.”

Reprinted with permission from Modern Woodworking.