Threaded-Rod Reinforcement for an Exterior Door

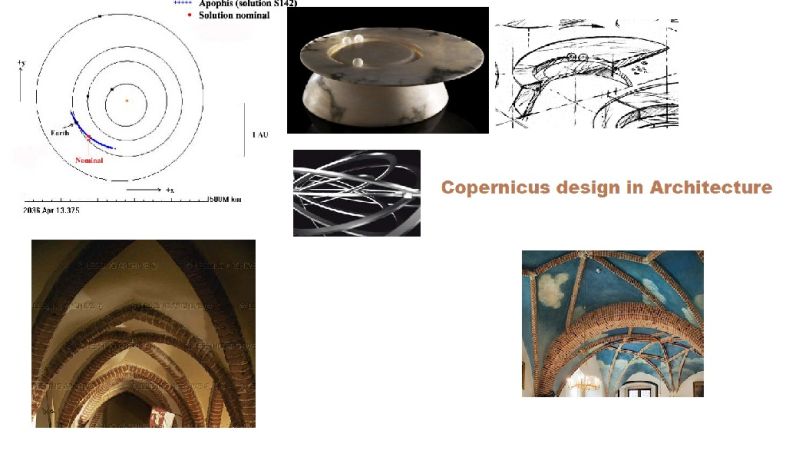

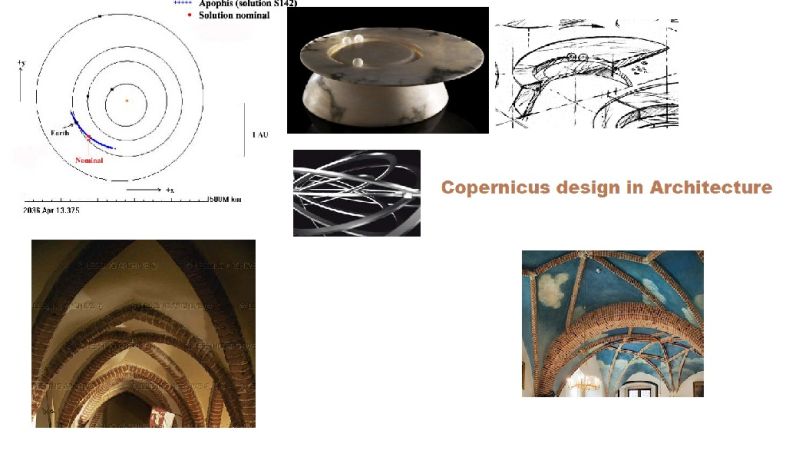

Woodworkers kick around a complex technical topic: whether and how to use steel to reinforce a wood door. (Also in this thread, a discussion of a "Copernicus" design pattern.)July 11, 2013

Question

I was asked today to do millwork shop drawings for a Copernicus design. Is anyone familiar with this design style?

Forum Responses

(Cabinetmaking Forum)

From contributor B:

It would seem that a Copernicus design in architecture would involve the use of heliocentric or eccentric circles. This would be given the name “Copernicus” from Nicholas Copernicus model of the solar system with the earth and planets revolving around the sun. Looks like you will still need to question the designer as to what exactly they expect.

Click here for higher quality, full size image

From the original questioner:

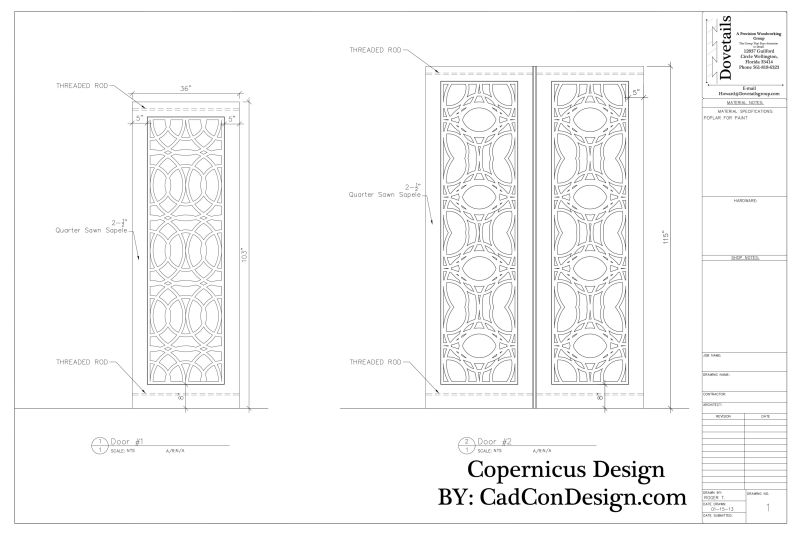

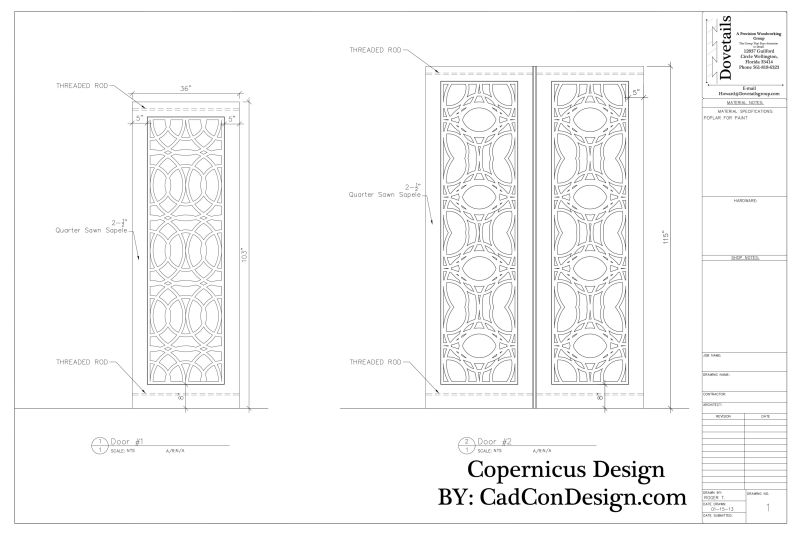

The designer sent us a hand sketch of the two types of door designs. She wants my client to provide a millwork shop drawing on. Here is what we came up with to clarify her hand sketch, which was more of a concept piece of artwork.

Click here for higher quality, full size image

From contributor O:

I would stay far away from the threaded rod thing. This is a sure sign of a misunderstanding of the movement of solid wood. If not solid wood, then it shows a lack of faith or experience in panel product and stability. While metal certainly has its place in woodwork, it is not necessary in the project I see. Are there any cross sections? Where are the joinery details? Nice elevations, but nothing can happen without meaningful cross sections.

From contributor L:

Totally agree with Contributor O. Don't know what the threaded rod is supposed to do. Generally a bad idea by someone that doesn't know what they are doing.

From the original questioner:

This is a single lite exterior door with 2-1/4" laminated sapele stiles and rails with mortise and tenon. The pattern is to be an inlay with 1/4" tempered glass behind. The threaded rod is to prevent racking since there is no real panel and the only wood in between the stiles and rails is the cut out pattern inlay.

From contributor O:

In all proper frame and panel work, the frame is structural, and the panel floats. That is, a well-made single light door with a panel of either glass, solid wood, panel product or other (metal, cork, mirror, etc.) will be just fine. The panels should not be counted upon to add rigidity to the structure. MDF, particle core or plywood panels can be glued if one chooses, since they have negligible responses to the inevitable RH changes. Adding a cope and stick to the tenon will also increase glue area and make things even stronger and help prevent water/weather intrusion, as well as yield professional results.

That is why I would need to see a cross section. The elevations are nearly meaningless except for a few basics. If I were to build these doors, I would have no problem providing a warranty with them. The Coastal Storm regulations in Florida will have no effect on the above reasoning.

The threaded rod shows a lack of faith and/or experience on someone's part. When I used to teach a beginning joinery class, we spent the first day making good stock and then joined it into a frame with square shouldered mortise and tenons, glued and clamped only. The next morning, we had coffee and then tried to get the frames apart. Everyone was shocked on two counts: that the joints were so strong as to destroy the wood before the joint failed, and that it was almost impossible to destroy the frame or rack it out of place.

From contributor R:

If a rod is used you would have to have a way of re-tightening it after a major swing in weather. The expansion of the wood is going to crush the fiber under the washer. When the wood shrinks back, the crushed fiber will not expand enough to tighten it against the nut. The nuts would only be tight about half the year around me.

From contributor O:

Contributor R is correct. Science raises its persistent head, no magic required. Let's carry the logic - the science - on through a bit and you will see what happens if the nuts are tightened when loose. Tighten the nuts when the RH (actually MC) is low. Then the MC increases, but the wood cannot expand any further, so the fibers crush a bit. (This is only on the cross grain wood - not long grain. In the current discussion, the stiles.) Then the next cycle comes around, and the wood shrinks, including the crushed fibers, and the nuts are loose. Tighten them, again, repeat as needed.

From contributor L:

That's why the threaded rod should not be considered the primary structure of the door joints. Compression set will occur no matter what after a few cycles. If the mortise and tenon joint fails the rod could be considered the backup but by then there will be a crack showing on the face.

From contributor O:

Good point Contributor L. Prior to modern glues the mortise and tenon joints were nailed, pegged, or wedged to hold if the glue failed. Compression set is what makes the threaded rod useless. Joint failure in doors should never be a problem. Good joints should be so basic to a door maker as to be easy and foolproof.